A Tale of Two Ideologies

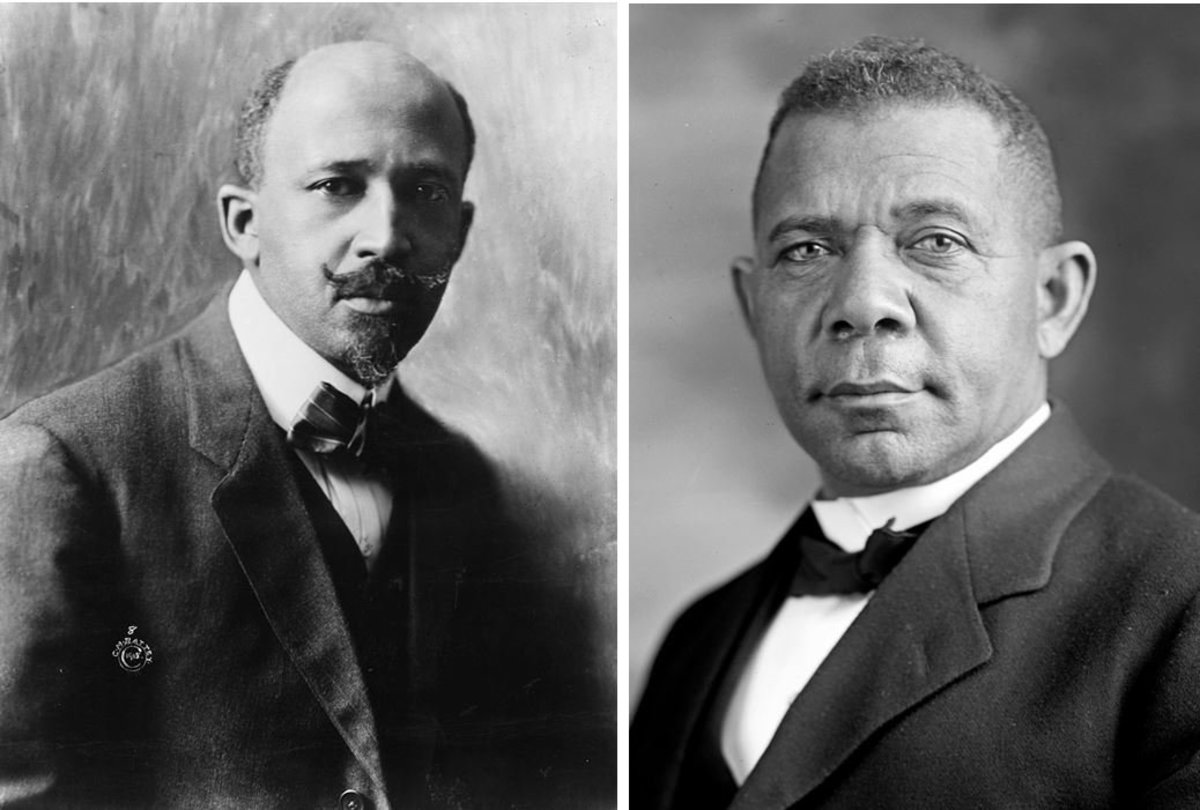

Booker T. Washington and W.E.B Dubois are two figures who are commonly recognized throughout the African American narrative. Both of their ideologies shaped the social structure of the black community during the early twentieth century, creating a divide in consciousness. My most recent discovery this week at the Archives, is Louis Armstrong’s personal interest in the philosophies of these two men. In the Epilogue of Brian Harker’s book; Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven Recordings, it is noted that Louis held strong feelings against W.E.B Dubois’ ideologies. For me, this discovery peeled back yet another layer of Louis’ personality; allowing me to analyze his perspective on politics and culture.

Born into slavery in 1856 in Franklin County, VA, Booker T. Washington’s philosophy advocated for self-help, racial solidarity, and accommodation. As an educator and reformer, he believed that blacks should gain an education in trades, agricultural skills, and the labor force; enabling them to be accepted by whites and eventually integrated. His perception was that honest work would gain blacks full citizenship by whites but would only be successful if blacks endured the “temporary” discrimination and concentrated on becoming hard working members of society. His theory resonated with many blacks and gained him support from whites who assisted in the funding for Tuskegee University.

W.E.B Dubois’ philosophy took a much more radical approach than Booker T. Washington’s. Born in 1868 in Great Barrington, Massachusetts, Dubois was an educator and civil-rights activist who helped found the Niagara Movement and NAACP. He believed that the black community could be elevated out of oppression if the elite of the race he called “The Talented Tenth” would advocate for social change. Dubois disagreed with Washington’s theory of acceptance; arguing that blacks should not conform to be accepted by whites, but rather agitate and protest to become equal and gain leadership. Dubois also asserted in his theory of “Double Consciousness,” the idea that because blacks have lived in an oppressive society, it is difficult for them to combine their identities as blacks and as Americans. He states in his book The Souls of Black Folk:

“it is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others… one ever feels his twoness, an American, a Negro; two souls, two thoughts, two unreconciled strivings, two warring ideals in one dark body, whose dogged strength alone keeps it from being torn asunder.”

After reading the epilogue of Brian Harker’s book, I became immensely curious about Louis Armstrong’s personal connection to these theories. Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven Recordings states that Louis received an autographed copy of J.A Roger’s 1947 historical survey World’s Great Men of Color. It continues to describe that Louis gave high regard to the book after reading it and even comprised a list of important chapters to read. He listed in chronological order the biographies of several men, including Booker T. Washington. At the end of this list he notes “S’All, No Du Boise” with the page number of the chapter, to confirm that it was not by accident that he did not list Dubois’ chapter. Harker states that Louis’ hostility for Dubois likely dates back to the 1920’s when much of the black community did not agree with his theory of the elite ten percent of blacks leading the race to equality. His sense of arrogance turned many away from supporting his cause because the popular notion was Dubois looked down on the rest of the uneducated race.

In contrast, Booker T. Washington was gaining support from the black community. His “commonsense morality” appealed to the majority of the race, especially those who leaned towards the conservative side of the spectrum. I believe that Louis Armstrong resonated with this ideology because he, too, believed in learning his craft and deterred from direct racial confrontation. Harker describes specific ideas of Washington’s theory such as

- Opportunity is all we want.

- Nothing comes to us easy. Hard work is the penalty we must pay for success.

- Make use of all idle time by learning some profession or trade; it may benefit you in years to come.

- Ability is what counts, and you cant take it away from one person.

Similar to Booker T. Washington, Louis Armstrong came from nothing and persevered to become a tremendous success. After analyzing their similarities, I understand why Louis may have sided with Washington over Dubois. He believed in hard work and opening doors for himself and others without jeopardizing his livelihood. Their focus was to be accepted by the people who held the power and opportunities they desired instead of retaliating against whites.

Despite the humble disposition of accommodation, Louis learned early in life that he had a strong dislike for people he deemed to have a “sense of Aires,” much like W.E.B Dubois. Harker affirms that Louis often spoke on this when describing his second wife Lil Hardin, a well-educated pianist, and fourth wife Lucille Wilson Armstrong. He learned his contempt for snobbery from his mother, who he claims spoke to everyone and was very humble. This distaste for people he considered to be snobbish has sparked my curiosity about his own self-image. Although he did not have an extensive educational background, he was surrounded by people of all walks of life; often many educated whites. To me, by mocking the educated blacks in his life, he shows a side of envy or tattered self-esteem. Perhaps it’s because of my own educational background and lack of understanding from Louis’ point of view, but as I continue to research him as a black man in the early twentieth century I feel like I’m going down a rabbit hole that introduces more complexities of the black experience than I anticipated.