“A Beautiful Night”: Salute to Satch, Newport Jazz Festival July 10, 1970

50 years ago tonight, George Wein turned the Newport Jazz Festival into a star-studded celebration of Louis Armstrong’s birthday, as he recently celebrated (what he believed to be) his 70th on July 4. Once again, we find ourselves departing a bit from the “That’s My Home” theme of this site to take you to Newport, using audio, photos and other archival materials found in our Research Collections.

As mentioned in a previous post, Wein attended the May 26, 1970 session for Louis Armstrong and His Friends and talked about the tribute that time. In the official press release for that album, Wein is mentioned as being “deep in his plans to make this year’s Newport Jazz Festival tribute to Louis Armstrong the ‘most rehearsed’ thing he had ever done.” Wein was quoted as saying, “I want to make it a real tribute–not just something put together. Louis is true culture.”

The original contract was saved by Louis and dated March 24 so he was aware of it. Here’s a rare glimpse at the business side of things (not pictured, but Louis also signed a rider agreeing not to appear in New England in June, July or August 1970 and on June 1, signed an agreement to have his set taped and broadcast on NBC’s Monitor radio program):

(For those who want to do the math, $6,500 in 1970 is $42,952 in 2020 dollars!)

Armstrong had been convalescing at home for much of the year as doctor’s didn’t want him to travel at all, but they finally relented and allowed him to fly to Los Angeles for his first big birthday tribute concert at the Shrine Auditorium on July 3. Armstrong woke up in L.A. on his July 4 birthday and then flew back to New York, spending the week resting after his first big trip in nearly two years.

At Newport, Armstrong arrived early to attend the rehearsal. All Stars clarinetist Joe Muranyi remained bitter until his dying day that Wein didn’t use the All Stars because they knew what Louis wanted (as we’ll see, he wasn’t wrong). Wein did have All Stars trombonist Tyree Glenn on hand but turned of Musical Director duties to Bobby Hackett. Hackett assembled a gaggle of great musicians, including trombonist Benny Morton, pianist Dave McKenna, bassists Larry Ridley and Jack Lesberg, drummer Oliver Jackson and fellow trumpeters Joe Newman, Ray Nance, Wild Bill Davison and Jimmy Owens.

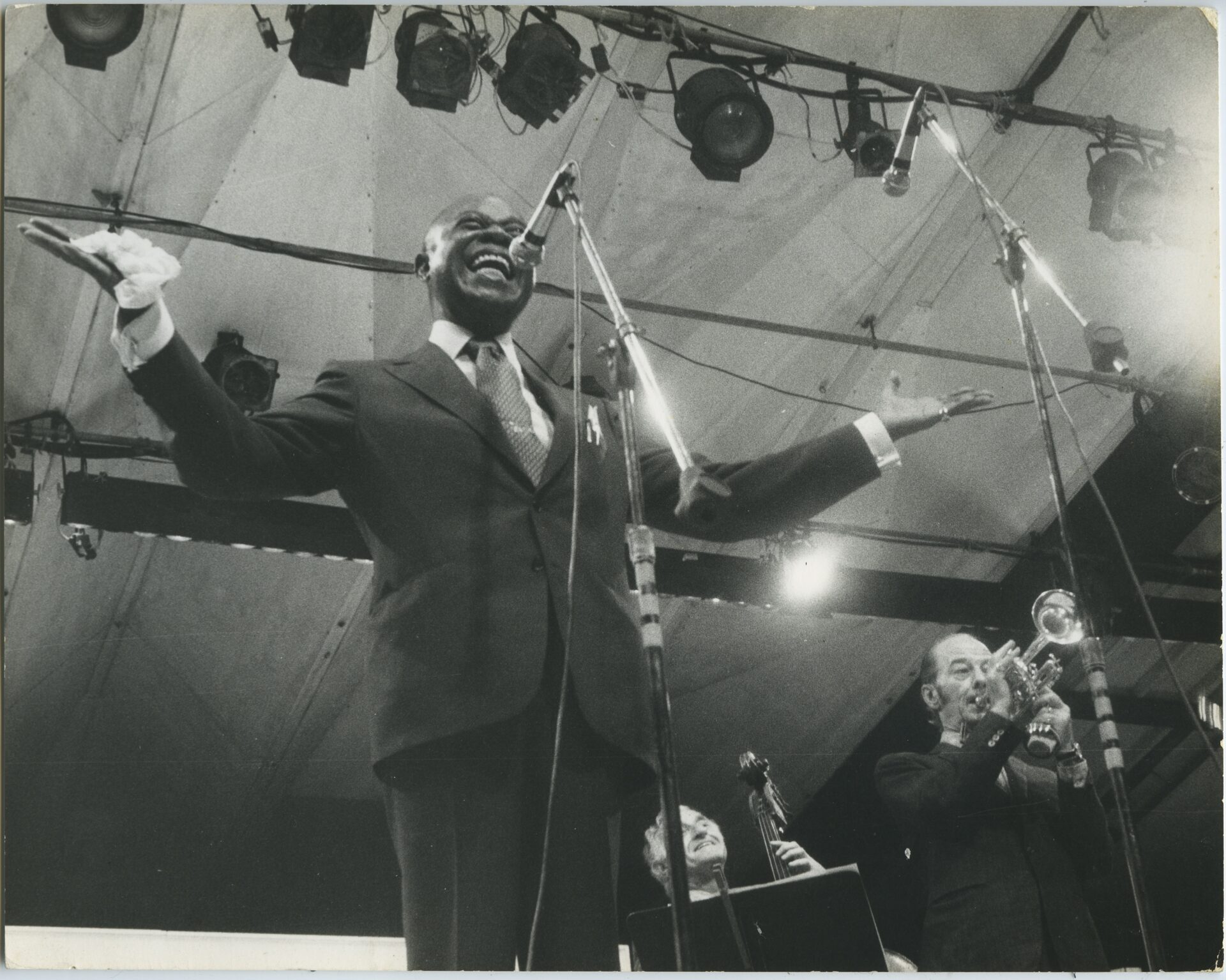

Jack Bradley was there from the start and was able to capture some wonderful glimpses of the rehearsal in color and black and white.

In addition, Wein also invited the Eurkea Brass Band and Preservation Hall Jazz Band to the proceedings, each loaded with New Orleans musicians, many of Armstrong’s generation. For those keeping score at home, the Eureka Brass Band included Percy Humphrey and Lionel Ferbos on trumpet, Willie Humphrey and Orange Kellin on clarinet, Jim Robinson and Paul Crawford on trombone, Capt. John Handy on alto saxophone, Allan Jaffe on sousaphone and Josiah “Cie” Frazier and Henry “Booker T” Glass on drums. The Preservation Hall set included trumpeter DeDe Pierce and his wife Billie on piano, in addition to Willie Humphrey, Handy, Robinson, Jaffe and Frazier.

Here are more Jack Bradley photos of Louis rehearsing with the New Orleans aggregation:

Finally, it was show time. Hackett led off with the “Trumpet Player’s Tribute” which culminated in Armstrong’s unannounced appearance, entering to riotous applause as he stepped to the mike to sing “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South,” “Pennies From Heaven” and “Blueberry Hill.”

Fortunately, Wein had a camera crew set up to catch the whole thing. Here’s “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South”:

After a short break, the second half of the tribute aimed to replicate the sounds of Louis’s childhood, with short sets by the New Orleans Classic Ragtime Orchestra (with Lars Edegran and William Russell), Preservation Hall Jazz Band and the Eureka Jazz Band before Mahalia Jackson took everyone to church with a roof-shaking performance. After whipping herself into a frenzy on an intense “Just a Closer Walk With Thee,” Louis appeared to finish it out with her as an emotional duet. As many of the other musicians from the first half gradually marched on stage, a torrential rainstorm hit. Sensing the end, Louis immediately launched into short but potent versions of “When the Saints Go Marching In” and “Mack the Knife.” Again, Wein’s camera captured (almost) everything; here’s the memorable “Closer Walk”:

Jack Bradley–who is visible in some of the footage above–was still there to capture some more beautiful photos of the evening concert:

And though the footage is silent, this Associated Press clip offers some different glimpses of Armstrong’s Newport tribute, including his final bows:

That concludes the actual concert portion of the evening but now it’s time to turn back to our “That’s My Home” theme and take a peak at mementos Louis saved from this very memorable evening.

First, Louis saved various newspaper clippings about Newport; here’s one from John S. Wilson, one of his most vicious critics back in the 1950s, who managed to write warmly about the tribute:

Then of course, there’s the music. As shown above, Louis had to sign a release to approve the use of his performances on NBC’s Monitor radio show. Soon after Newport, Monitor sent him tapes of the two broadcasts they dedicated to his Newport tribute. Louis didn’t even make a collage, instead summing up what was contained on the tape right on the outer box (this reel also includes his first dub of Louis Armstrong and His Friends, released July 4):

It wasn’t long before Louis pulled out his tape catalog and wrote down the contents of the reel:

As a gift to our loyal readers on this 50th anniversary, we’d like to share the audio of both Monitor reels, as dubbed by Louis! Here’s the first part:

LAHM 1987.3.644

The first part opens with “Panama” by the Eureka Brass Band, who are soon joined by host Murray the K, who sets the scene. Murray then makes a big faux pas, crediting Bobby Hackett for a version of “Mack the Knife” that was actually a feature for Jimmy Owens! Ray Nance’s “I’m in the Market for You” follows before Murray the K has a conversation with Jim Mendez about the trumpet tribute to Armstrong. The New Orleans Classic Ragtime Band then plays “St. Louis Tickle” before Joe Newman ends the first part with “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans.”

Then part two:

LAHM 1987.3.645

Part two opens with Dizzy Gillespie doing “Pops’ Confessin’” (which Wein later claimed Louis hated). Wild Bill Davison hilariously introduces “Them There Eyes,” which has some great Dave McKenna before Murray the K cuts them short. We then get the full audio of “Just a Closer Walk With Thee” (a different mix that allows us to hear Louis summoning Bobby Hackett before a longer ending not in the film) before a surprise at the 18:00 mark: “Hello, Dolly!” As alluded to earlier, Joe Muranyi was upset that the All Stars weren’t invited and Wein’s final film edited out “Dolly.” Why? Well, just listen: for all of that talent, “Dolly” is a train wreck as no one can figure out what key Louis is in except for Tyree Glenn and Hackett. Eventually Jackson’s organist (most likely Ralph Jones) finds it and it sounds like Wein might take over the piano but Louis pulls the plug early on, even attempting to obscure the confusion by pointing out the dancing of “grand marshall” Willie Humphrey. Wein conveniently edited out this sequence in the film but it’s good to have as evidence that even the greats weren’t perfect!

Eventually, Louis received reels of the complete evening at Newport (without the interruption of Murray the K). We won’t share those here (though you can listen to the complete evening if you’re a member of the Wolfgang’s Vault site) but we will share Louis’s handwritten catalog sheets, always a delight to read:

Louis was proud of the tapes and especially knocked out by Jimmy Owens’s performance of “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” which was spent almost entirely in the low register of his horn. On August 25, 1970, Louis appeared on the David Frost Show, where Owens appeared in Dr. Billy Taylor’s house band, and discussed it:

LAHM 1987.3.446

Also in the summer of 1970, Louis was sent some photos from the Newport tribute. He immediately placed images of himself with Bobby Hackett and Mahalia Jackson in a scrapbook he had been working on since the previous year. We already shared these images in our three-part exploration of this scrapbook but it’s worth showcasing them again here for the anniversary:

And finally, a tape box collage Louis made in early 1971 made up of another photo of him embracing Mahalia:

We’ve been spending a lot of time commemorating the 50th anniversary of Louis’s various activities in 1970 but if there’s a common theme to everything, it’s that Louis needed this last hurrah for his own psyche as much as anything else. He hit rock bottom in intensive care in Beth Israel Hospital in March 1969, purging his feelings into a dark manuscript we covered in our look at Louis during the Civil Rights era. He was then dealt a double blow by the death of longtime manager and friend Joe Glaser and the news that he could no longer play the trumpet. If he had died in 1969, it would have been a tragic ending to an incredible life.

But in 1970, he began returning to the public life and, perhaps seeing how close the world came to losing him, people stopped taking him for granted and now relished everything he did. He made reel-to-reel tapes at a furious pace, making nearly 200 in the last year-and-a-half of his life. He compiled multiple scrapbooks, often filling them with photos of events he had just attended. He recorded the emotional Louis Armstrong and His Friends album, featuring contemporary sounds arranged by Oliver Nelson. He had star-studded birthday celebration on both coasts, each attended by jazz royalty, all of whom performed for him and paid tribute to him. And the July 9, 1970 issue of Down Beat was a full-blown tribute to Armstrong, highlighted by “Roses For Satchmo,” a five-page spread of nothing but musicians ranging from Miles Davis to Ornette Coleman to Tony Bennett to Eddie Condon paying tribute to Armstrong. When Louis saw it, he wrote to Editor Dan Morgenstern to tell him that it knocked him “on his ass”; Dan still has the letter, which he showed in this video shot by Michael Steinman in 2019. Upon seeing Dan at Newport on July 10, Louis planted a big kiss on him as Bobby Hackett looked on, a moment captured in a memorable photograph by Harriet Choice.

Louis still had another last last hurrah in him, getting permission to start playing the trumpet again in September and going back on the road, working himself to death but going out on his shield before passing away on July 6, 1971, less than a year after the Newport night. But tributes such as Newport and in Down Beat at least allowed Armstrong to know beyond a shadow of a doubt that he was truly loved by his many peers and disciples in the jazz community and the music community as a whole.

With that said, it’s only appropriate to end not with something from Newport but rather the “Roses for Satchmo” tribute, which knocked Louis on his ass 50 years ago this week and is still a wonderful tribute to a true American icon.