Louis Armstrong’s 1969-1971 Tapes: Reels 121-125

We’ve said this a few times in recent months, but this might be the most action-packed of all the posts in this ongoing series. No preamble is necessary, let’s jump in!

Reel 121

Accession Number: 1987.3.421

In our last post, we shared tapes Ivan Mogull sent to Louis of a few dozen songs to be considered for the album Louis “Country and Western” Armstrong. Eventually, Armstrong chose his favorites, which were compiled on this reel. At first glance, “Country-Western Music Recorded By Louis Armstrong” seems to imply that this was a dub of the finished Armstrong LP, but no, it’s Armstrong’s compilation of songs to study before the record dates (and for those who know the album, he didn’t get to all of these, but it’s still interesting to see which ones spoke to him). The order on the tape is as follows: “Ramblin’ Rose” (Sonny James), “Crystal Chandelier” (Charley Pride), “The Easy Part’s Over” (Charley Pride), “Just A Girl I Used to Know” (George Jones), “Running Bear” (Sonny James), “You Can Have Her (Jim Ed Brown), “If You Were Mine, Mary” (Eddy Arnold), “Itty Bitty Heart” (Claude King), “Wolverton Mountain” (Claude King), “Almost Persuaded” (David Houston), “Runnin’ Bear” (Sonny James), and “Crazy Arms” (Ray Price). At that point, the 1971 Chrysler-Plymouth “Comin’ Through” commercial plays–was Louis perhaps up for recording that at some point? It’s possible, but after, it’s back to a few more country sides, including Leroy Van Dyke’s “Black Cloud” and “Five Steps,” followed by two unknown demos, “Those Wonderful Days” and “Confidence.”

Back in June, Armstrong had appeared with Lauren Bacall at a Rainbow Room event to promote the New York City Summer Festival. Multiple photos from the event can be found in Louis’s scrapbooks and eventually, his tape boxes; here’s one he created towards the end of his life:

At the time of that event, Bacall was starring in the Tony-winning Broadway musical, Applause, which opened March 30, 1970. Bacall most likely laid a copy of the original Broadway cast recording on Armstrong at the Rainbow Room and Armstrong finally got around to recording it on Reel 121. With a little bit of space left, Armstrong again reached for The Glenn Miller Story soundtrack we saw on Reel 120, but only got through “Basin Street Blues” and part of “Otchi-Tchnor-Ni-Ya” before running out of time:

It’s another collage-less week, but don’t worry, the type of work typified by the Bacall box above will return in future posts! For now, here’s some plain black boxes with Armstrong’s handwritten labels:

Reel 122

Accession Number: 1987.3.422

With Reel 122, we’re back firmly in the territory of Louis listening to his own music–and most likely, playing along with it. He now had a real reason for building his chops back up–he had a gig lined up! On June 17, 1970, Armstrong signed a contract to perform for two weeks at the International Hotel in Las Vegas from September 8 through September 21 (Elvis Presley ended a run there on September 7; wonder if they ran into each other!). It would be Armstrong’s first extended engagement since September 1968 and he’d have his All Stars with him–but that wasn’t enough. Armstrong wanted to play trumpet again.

At some point in the summer of 1970, Armstrong was feeling strong and wanted to prove to his doctors that he was ready to play trumpet again in public. Dr. Gary Zucker suggested coming over one day and examining Armstrong as he played trumpet along with some records, but Armstrong said no, the only way to really tell if he was back was if he could play with his band, the All Stars. Trombonist Tyree Glenn, clarinetist Joe Muranyi, and and pianist Marty Napoleon (maybe more, but we at least know that these three were definitely there) came out to the House and a jam session commenced in the Armstrong’s living room. According to Muranyi, Armstrong “played like a man possessed.” Upon conclusion, Dr. Zucker examined everything and gave him a green light.

All of the above is true but I’ve placed this story ahead of Reel 122 because I’m pretty sure Armstrong spent a lot of time before the International Hotel gig playing along with his tapes and this seems like a candidate for such a reel. It opens with more from Louis Armstrong and His Friends before becoming a hodge-podge of recordings from over the years, including tunes with the Mills Brothers, with Luis Russell’s Orchestra, with Oscar Peterson, and on Side 2, a selection of his OKeh recordings spanning 1925-1932, with a Decca single of “Sweethearts on Parade” and “Cut Off My Legs and Call Me Shorty” thrown in for good measure. Here are the catalog pages and the tape box scans:

Reel 123

Accession Number: 1987.3.423

Okay, we promised audio in this post and we’re about to make good on that promise! Armstrong liked to record at 3 3/4 speed to maximize the amount of space he had to record but he really milked this reel for all it was worth as both sides weigh in at roughly 3 hours and 10 minutes apiece, making for a nearly 6 1/2 hour reel! And honestly, we could have done an entire series of posts just about this tape because it’s so rich, but we’ve cherry picked what we think are the best moments to share today.

The first chunk of Side 1 finds Armstrong catching up on his 70th birthday television tributes. There’s some fade-ins and outs so I’m assuming these were professionally edited and sent to him either by his friend Tony Janak or the Direct Recordings company. We’ll open with NBC’s Today show for a short tribute by Joe Garagiola and a photo montage set to Louis’s 1941 recording of “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” (we don’t know which photos were shown, obviously, but it’s always nice to hear that special version of “Sleepy Time”):

LAHM 1987.3.423

Next, a KCBS report on Louis’s 70th birthday concert at the Shrine Auditorium by Ruth Ashton Taylor (who turned 100 in April!). Taylor includes a short conversation with Armstrong, where he talks about being in intensive care and gets asked about playing the trumpet, telling Taylor his doctors cleared him to play in public after September. Louis’s last line, “As long as you can breathe and get out of that bed, you’ve got a chance,” is particularly affecting:

LAHM 1987.3.423

Sticking with these short pieces, here’s another news report on Armstrong’s July 4, 1970 concert at the Shrine, with audio from that show of Louis cutting the cake and singing “Hello, Dolly!”

LAHM 1987.3.423

Sticking with the 70th birthday coverage, here is my favorite clip of all, a piece Bill Stout did for CBS. The main event is an interview Stout did with Armstrong where once again, Louis is asked about “not being able” to play the trumpet. Something about Stout’s wording sets Armstrong off and he gets very testy in his response, showing how prideful–and tough–Armstrong remained until the end:

LAHM 1987.3.423

If you couldn’t make it out, here is a transcription of the exchange:

Bill Stout: How do you feel about not being able to blow?

Louis Armstrong: I never said I was not- I blow everyday at my house, one hour before my meal.

Bill Stout: Yeah, but you’re not supposed to work.

Louis Armstrong: Well, I don’t have to work. I’ve got enough money, I don’t have to work. I play when I want. I still want to, doctor said don’t do it and I don’t do it. But I can play- I can warm up one hour and go right back to work right now. But you don’t have to do that. If he says, “No,” that’s no, ain’t nobody else can- I don’t care what they think. And they’re not appreciating my singing, my biggest records are singing anyway. That’s right, I don’t want to be crude about it, but I didn’t like the way you asked me, you know?

Bill Stout: I didn’t mind that.

Louis Armstrong: Not being able to blow!?

Bill Stout: I’ve enjoyed so much hearing you blow.

Louis Armstrong: Every time I breathe I can blow that horn, get right out of bed, you know?

Bill Stout: But- but why do you think- why do you think, when you talk to the other people who are doing all of those things, why do you think you were so far ahead

Louis Armstrong: Ask the public. I- I don’t know. I’m like Joe Louis when they asked him, “When did you think you were gonna knock that fellow out?” He said, “When I signed up for the bout.” That’s what he said. And I don’t go, [pats himself on the back] on my shoulder, but I can listen to–they listen to me, I listen to them. I can tell the minute he hits two notes whether he’s playing right, or he ain’t going to play it right, or- but that’s his business.

Bill Stout: But, you know, there really haven’t been many musicians in our time, I suppose Sir Thomas Beecham, and the Beatles, and Louis Armstrong, and that’s about it who are world figures, and you are.

Louis Armstrong: Well, okay, I’ll buy that.

Bill Stout: Yeah, but how is-

Louis Armstrong: I didn’t strive for it. I wouldn’t get it if it wasn’t real.

Bill Stout: How is it to live that way?

Louis Armstrong: Well, I mean, what’s wrong with it? I’m living the same every day. The way I live, I mean, everything in my house is good, and what I mean- you don’t see me with no big estates and yachts.

Bill Stout: No.

Louis Armstrong: Well, that ain’t- that ain’t going to play my horn for you, but a lot of them do that, and they come from taking a walk around their estate, they so damned tired they ain’t got no breath to blow a horn!

*************

After all of those short birthday tributes, Armstrong settled in and dubbed a 90-minute radio retrospective of Armstrong’s career on Chuck Cecil’s show, The Swinging Years. In addition to lots of music, Cecil also had interview excerpts from Joe Darensbourg, Kid Ory, Earl Hines, Leonard Feather, Barney Bigard, Alton Purnell, Lionel Hampton, and Louis himself. It’s a show worthy of sharing–but for whatever reason, Armstrong’s dub on this tape is inferior sound quality. Thus, we’re skipping it now but it returns in better fidelity on a future tape so we’ll save that for another day.

The next segment is something we’ve actually shared in the past and we urge you to check it out if you have the time. On January 8, 1970, Jim Grover called Louis Armstrong at home and asked him about Bix Beiderbecke. Louis spoke for about 9 1/2 minutes and Grover used excerpts of it in an episode of Bix: A Biographical Radio Series on Miami University Radio. On this part of Reel 423, Grover sent Louis a copy of the complete first episode of his series (you can hear them all here) and followed with the raw audio of his phone call with Armstrong. We shared that in a 2020 post, “Satchmo Always Loved Bix,” so head over there to hear the audio of this touching phone call.

We’re still not done with Side 1 of Reel 123 (wait til you see the catalog pages). Armstrong actually broke the phone call up in parts and filled the space with dubs of his 1967 Italian recordings, as well as an unissued duet with Velma Middleton on “Mack the Knife” that appears on many 1969-1971 tapes (perhaps he was blowing along with this tape, too).

On July 22, 1970, Louis appeared on The Merv Griffin Show, an episode where the video apparently no longer survives, so we’re happy to share the watermarked audio, the first time it’s probably been heard since it originally aired. The episode opens with Griffin celebrating the 76th birthday of his regular guest, singer and actor Arthur Treacher, who also mentions his famous chain of fish and chips restaurants. Armstrong then comes out and sings “The Bare Necessities” before joining Griffin and Treacher to talk about his 70th birthday tributes at the Shrine and he Newport Jazz Festival. It’s a fun interview, with Louis reminiscing about stopping the civil war in Leopoldville, meeting Lucille and courting her, and even sharing a bill at the Click Club in Philadelphia with Griffin when he was singing with Freddy Martin.

After the commercial, Griffin promotes a Madison Square Garden concert set for October 15 that would benefit the newly established Louis Armstrong Educational Foundation “for higher education for underprivileged kids,” a concert that sadly never came to pass. After a discussion of the album Louis Armstrong and His Friends, Armstrong his and Luis Russell’s composition “Back O’Town Blues,” mentioning he was getting “a little taste from ASCAP” (remember that Armstrong was singing more of his original compositions than ever before on television, ever since Joe Glaser left him all of his music publishing rights after he passed in 1969). Armstrong sings the hell out of it and adds a bunch of extra choruses, borrowing some of the verses he used to sing on “St. Louis Blues,” a chorus Velma Middleton used to feature, and even some scatting. We’ve let the audio run to include a following segment with Shelia McRae, where Louis is involved–enjoy!

LAHM 1987.3.423

Side 1 ran out before Armstrong could complete his dub of the Griffin show, but he began Side 2 with a few more minutes featuring guest Rocky Graziano, before he stopped recording (or perhaps that’s all they sent him as it does seem to fade).

LAHM 1987.3.423

Before we get to the rest of Side 2, let’s share some catalog pages. On page 168 of his , Armstrong simply listed all the songs heard on this reel, including those in the Chuck Cecil tribute and the Bix Beiderbecke show:

The reverse of the page is a mystery as Armstrong originally seemed to denote an empty side, but once filled up, he put a big “X” over the page and noted it was actually “Continued”:

Armstrong then inserted “Page 168 1/2” and formally cataloged all of those 70th birthday segments and started his list of songs heard on this tape, the list continued two pages up. So yes, we’re technically presenting these out of order, but with “Page 168 1/2,” this is actually how it lays out in his tape catalog so we’re going with that:

One week after Armstrong appeared on The Merv Griffin Show, he was back on television, appearing on The Dick Cavett Show on July 29. For those who have followed this series for awhile, we discussed and shared Armstrong’s January 13, 1970 appearance on Cavett in a previous post, as that episode featured Armstrong’s return to trumpet playing in public–a mostly sad excursion that resulted in him putting the horn back in its case (in public) for the next nine months. In July, Armstrong left the trumpet at home but was in jubilant form on two vocal specialties, “You Rascal You” and “Someday You’ll Be Sorry” (another original composition that inspires another ASCAP line!). But it’s the interview segment that is most notable, mainly for a dramatic telling of racial incident that occurred at the Suburban Gardens in New Orleans in 1931. Video of that story can now be seen in the wonderful documentary, Louis Armstrong’s Black and Blues (streaming on Apple TV+) and on the Dick Cavett Show’s YouTube channel. Here’s the video of just the interview segments:

And here’s the audio of Armstrong’s entire appearance, with both songs, and a taste of following guest John Byner at the end:

LAHM 1987.3.423

After the Cavett appearance, Armstrong filled out the rest of Side 2 with dubs of two more 70th birthday tributes, both on the long side and both with some sound quality issues that don’t really make them worthy of sharing here (also, no interviews with Louis, just commercial recordings). First, Willis Conover Voice of America tribute, broadcast on July 4, 1970 and, we assume, was dedicated “To Pops, With Love,” as that’s what Armstrong has copied in his catalog description. That’s followed by a salute to Louis that was broadcast on KRHM in Los Angeles on June 26, 1970 and hosted by Gary Hammond and Don Brown, who played records (including numerous excerpts from Lil Hardin Armstrong’s spoken word Satchmo and Me LP) and got in many plugs for the concert at the Shrine.

Here are the (multiple) catalog pages that sum up Reel 123–what a tape!

Now, it probably feels like we’ve spent enough time with Reel 123 as is but it’s time to introduce a new part of the saga: Louis Armstrong’s cataloging methods. Up to this point, we’ve spent the last two years sharing Louis’s catalog pages, which seem pretty straightforward. But Armstrong actually seemed to have kind of a redundant method to his madness as when he’d make a tape, he’d handwrite the contents on a series of his “Lose Weight the Satchmo Way” diet charts! Upon completion, he’d fold the pages and stick them in the box.

Then, on a rainy day or when he had time to catch up, he’d pull out the folded sheets and copy the contents listings into his spiral tape catalog notebook. We’re quickly approaching the end of Louis’s notebook listings and though we have the above pages for Reel 123 to share, this is the first instance where the original box contained eight handwritten pages! This is going to be the primary method of sharing Armstrong’s cataloging in the very next post, so we might as well get used to it now–here goes!

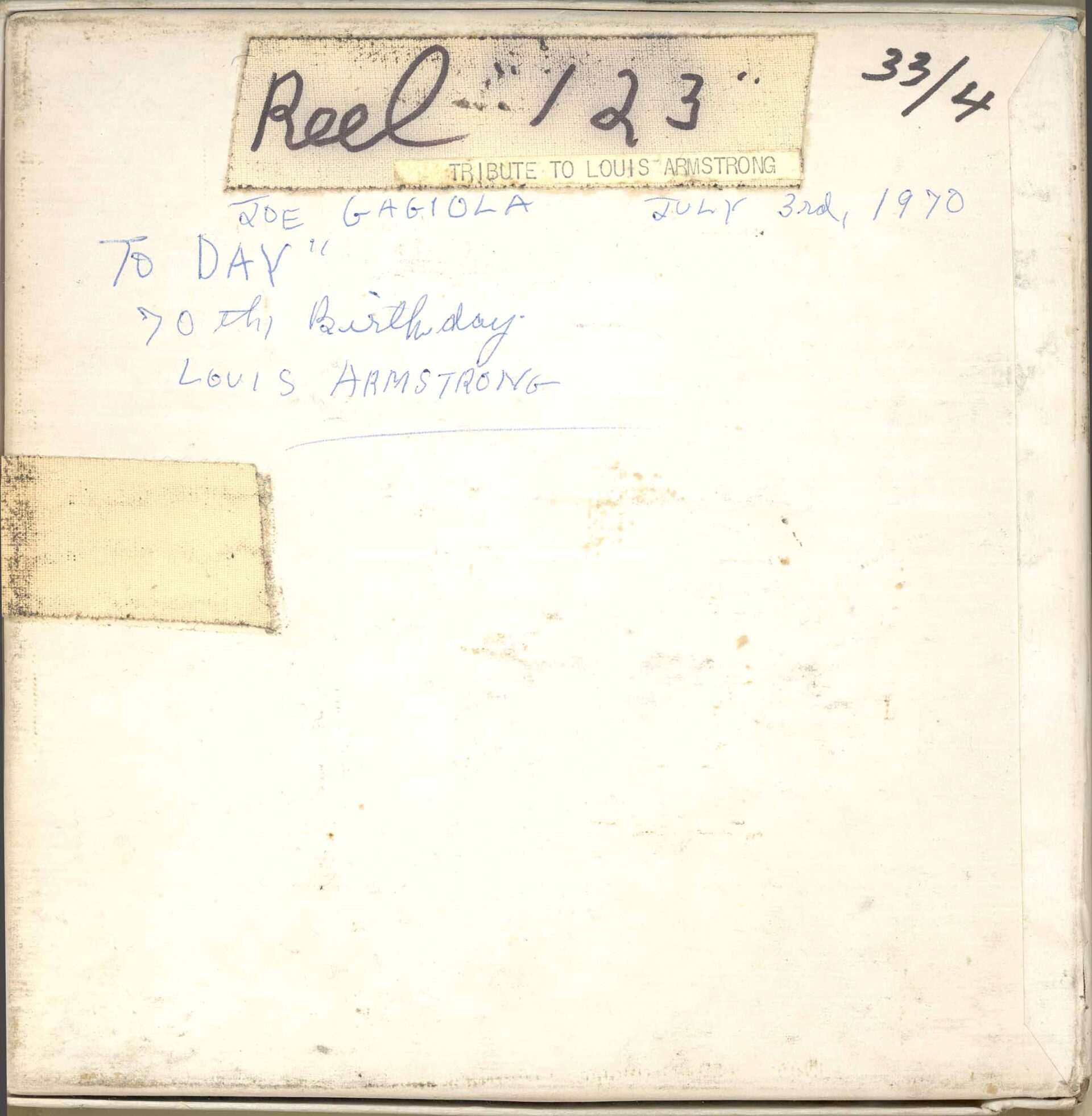

The original box for Reel 123 housed audio of Louis on The Mike Douglas Show, but Louis crossed that out and repurposed a “TRIBUTE TO LOUIS ARMSTRONG” label that sure seems appropriate for this particular tape:

And with all of the content across over six hours of tape–Bix Beiderbecke, Merv Griffin, Dick Cavett, Chuck Cecil, Willis Conover–Armstrong only highlighted the first one on the back of the box, listing Joe Garagiola (not “Gagioloa”!) and his Today show tribute of July 3, 1970:

Reel 124

Accession Number: 1987.3.424

It might seem tough to top Reel 123, but Reel 124 might be the most famous tape in our entire Archives. In the summer of 1970, Max Jones, John Chilton, and Leonard Feather collaborated on a short paperback book, Salute to Satchmo, published in time for Armstrong’s 70th birthday. Jones was inspired to keep going, especially since he already had a few extended letters from Armstrong to draw from. He wrote Armstrong in the summer of 1970 with a list of questions on subjects ranging from Little Rock, his second wife Lil Hardin Armstrong, his time Fletcher Henderson, and had he ever met Django Reinhardt, to the formation of the All Stars–and what exactly he remembered from being arrested for marijuana in 1930.

Armstrong began writing his letter to Jones on August 15, 1970. It took him some time to finish; he mentions early on that he had to appear on The David Frost Show on August 25 and he also talks about rehearsing at home with his All Stars, as discussed earlier. When he eventually finished, he must have known he had really created something special because he sat down at his desk in his den, turned on his tape recorder, and read the entire letter onto tape. Armstrong being Armstrong, he occasionally abandoned the text and improvised; at one point, upon stumbling over a word, he corrected himself and said aloud to no one in particular, “See, I scribbled it down so I could remember the rudiments, you know And I’m running over myself here. But anyway, you got it on paper so it doesn’t make a difference. I’m putting it on tape, you know for my posterity, or whatever you call it.”

Armstrong–less than a year before he died–was in the mood to set the record straight, on Lil, on Coleman Hawkins, on King Oliver, on Henderson, and on marijuana. The latter topic was especially controversial and something Armstrong never discussed publicly and though he was alone in his den, he had to know his words would go public. What inspired him to do so? I have my own theory: on that July 29, 1970 episode of The Dick Cavett Show, the third and final guest was conservative pundit William F. Buckley. The subject turned to the legalization of marijuana and Cavett, Buckley, and even John Byner got involved in the discussion–but Armstrong sat silently, not contributing to the conversation in any way. What could have been going through his head as these three white intellectuals were debating something he had been using for decades, something he had once been arrested for?

Thus, perhaps feeling the topic was going mainstream–and breathing a sigh of relief that Joe Glaser was now deceased–Armstrong went on the record to Jones about his feelings on marijuana. This brings up a second question–did Armstrong know his days were numbered? He seemed very healthy in the summer of 1970 but perhaps he knew he wouldn’t be around much longer and wanted to get these feelings out before it was too late. Sure enough, Jones’s eventual book, Louis, didn’t get published until just after Armstrong died in 1971. If he was alive, would he have been questioned about it in all of his television appearances? One wonders…

Anyway, we’re not going to dabble in that subject matter as the letter can be read in Jones’s book and excerpts can be heard in Louis Armstrong’s Black and Blues. But in 2008, the Armstrong Estate approved of an edit of the Max Jones letter for a 2-CD set that is now out-of-print. Here are those edited segments, just to give a taste of this important document:

LAHM 1987.3.424

LAHM 1987.3.424

And here is the close of the letter, which we call “Philosophy of Life” and play during every tour of the Louis Armstrong House Museum:

LAHM 1987.3.424

Here’s the bare-bones catalog pages:

And the tape box, with Max Jones getting top billing:

Reel 125

Accession Number: 1987.3.425

With Reel 125, we’re approaching new territory. Believe it or not, this is the next-to-last tape Armstrong catalogued in his index book and both Reel 125 and Reel 126 have contents that don’t quite line up with what Armstrong writes here. To set the scene, here are those pages:

For Reel 125, he only mentions Lucille Boyd of Norfolk, but Boyd doesn’t appear until Reel 128. He also writes “Empty” for the rest but the reel is far from empty. As mentioned in our discussion of Reel 123, this represents the next-to-last entry in Armstrong’s tape catalog binder; from here on out, we only have the folded up diet charts that were found in each box after Louis passed away. Again, he most likely individually catalogued the contents of each tape on separate sheets of paper (diet charts) which he stuck in each individual box. At some point in 1970, he began copying the contents of those loose sheets of paper into this notebook and died in 1971 before completing it, only getting as far as Reel 126. Thus, the above catalog pages are useless but Reel 125 did have two folded up diet charts inside which tell the full story:

As noted above, Reel 125 actually starts with an episode of Arthur Godfrey’s WCBS radio show with special guest Lionel Hampton, who reminisces about his time with Armstrong and plays a little “Twelfth Street Rag” with Godfrey on ukulele and a swinging rhythm section (including, we guess, Remo Palmieri on guitar based on Godfrey’s mention of “Remo”). Though Armstrong isn’t present, we feel it’s still worth sharing (and listen to the beginning as everyone present rave over a new Neil Diamond record):

LAHM 1987.3.425

We have also zoomed ahead way in the future, but don’t worry we’ll make up for lost time in future posts. Reel 124 featured the letter to Max Jones, which Armstrong began on August 15, 1970 and probably finished in September and Reel 125 opens with Hampton telling Godfrey he was attending a testimonial dinner for Armstrong that took place at the Waldorf-Astoria…on November 8. What happened in between? There were the two weeks at the International Hotel in September, then a trip to Los Angeles to film The Flip Wilson Show, a trip to Nashville to film The Johnny Cash Show, and a trip to England for a David Frost “Spectacular” command performance for the royal family. And according to Hampton, Armstrong came back home and made a beeline for Hamp’s gig in Amityville, Long Island, singing with the band until 3 a.m. Armstrong was feeling his oats–and it turned out to be a last hurrah. After the Waldorf dinner (which we’ll also get to in a future post), Armstrong went off the grid for the rest of November and much of December 1970, with no television appearances or outside engagements. We assume he spent much of his time resting–and making tapes.

Thus, eventually we’ll go backwards and hear highlights from some of the events listed above but Armstrong began Reel 125 with that November broadcast and followed it with a dub of a Swedish LP, Swinging the Louis Armstrong Songbook, performed by Swing Society and produced by Gösta Hägglöf. Hägglöf was close with Jack Bradley, who provided the cover photo of Armstrong, taken during the Dukes of Dixieland session at Webster Hall in May 1960:

Hägglöf enlisted Bradley’s help in asking Armstrong to come up with a list of tunes the he composed. Armstrong wrote such a list, which appeared on the back cover of the album:

Now here we go into speculation territory again, but the final recording session for this album took place on October 7, 1970–it would almost take a miracle for Hägglöf to turn a finished product around quick enough to get into Armstrong’s hands by November. Armstrong most likely received it at the start of 1971, inspiring him to write this touching letter on February 10 of that year:

(It should be pointed out that Armstrong’s urging Hägglöf to “Keep up the good works” inspired the Swedish banker-by-day to devote all of his free time to Armstrong and his legacy. When he passed away in 2009, he willed his entire, massive Armstrong collection to the Louis Armstrong House Museum.)

When Jack Bradley visited Armstrong for the final time in June 1971, he snapped a photo of Armstrong listening to Hägglöf’s LP:

(It’s funny to point out that Armstrong sent Hägglöf that handwritten list of his compositions but when he got the album, he actually couldn’t remember some of the titles of the songs he wrote! If you check out page two of the handwritten pages found in the box, Armstrong writes “Can’t remember the name?” for “Heart Full of Rhythm”; “Some Good Old Blues” for “Knockin’ a Jug”; “I Ain’t Rough – Hmm?” for “Canal Street Blues” and “A Familiar Tune” for “Wild Man Blues.”)

As for Side 2 of Reel 125, it was an all-classical affair, Armstrong dubbing two LPs, the first Eugene Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra’s version of Richard Strauss’s A Hero’s Life (Ein Heldenleben) from 1961, and the second, Jan Smeterlin’s Chopin – Nocturnes, an Epic release from 1956.

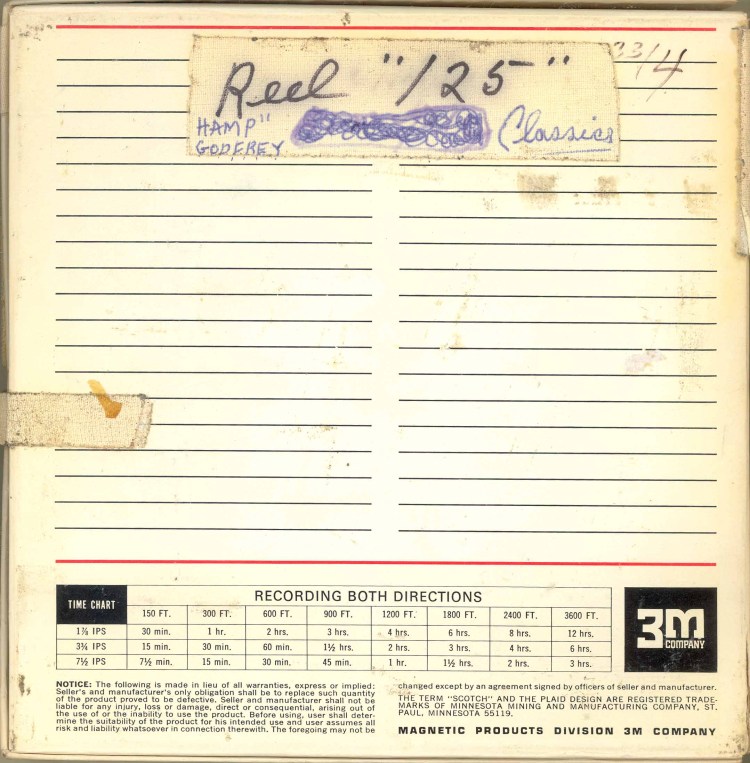

The box for Reel 125 is on the money, with Armstrong noting Lionel Hampton’s appearance on Arthur Godfrey’s show, and the abundance of classical music (“Classics”) on Side 2:

I feel like I’ve said this a few times but maybe that the most action-packed post of this series–I sincerely hope you’re enjoying them (though I don’t know how many folks have reached the end of this one to read this message!). Yes, we’re nearing 1971 and yes, we’re nearing the end of Armstrong’s tape catalog binder–but he still had about 45-50 tapes left in him so we’ve still got at least 10 posts left in this series, enough to take us into 2023 before we belatedly resume telling the saga of Louis and Jack Bradley. Thanks for reading!