Louis Armstrong’s 1969-1971 Tapes: Reels 161-165

Our previous post was packed with content and today’s won’t be very far behind as Louis continues to reach back to tapes from the 1950s and 1960s and come up with almost nothing but gold. Let’s not waste any time and dive straight in.

Reel 161

Accession Number: 1987.3.459

Reel 161 is a bit confusing, but it seemingly reintroduces us to the figure of Lloyd Von Blaine, Louis’s PR man in 1970 who was part of a memorable tape we chronicled here. Von Blaine doesn’t speak on this one, but perhaps he made it for Louis? The names “Lillian and Harold” are also listed on the catalog sheet. Lillian and Harold Howland were a couple from San Diego that made a tape with Von Blaine in September 1970 that made up Armstrong’s Reel 135 (covered here) but they’re not on Reel 161. Perhaps Louis was looking at that reel and got confused?

What is on the tape is a radio tribute to Louis definitely from the latter part of 1970 or early 1971 as it includes selections from Louis “Country and Western” Armstrong, which was released in October 1970. But again confusion reigns: Louis writes “Al Jackson,” who was a disc jockey in Los Angeles–but on the back of the catalog page, Lucille Armstrong wrote “Harold Jackson” and his address at WLIB radio–Harold Jackson being pioneering African American disc jockey Hal Jackson, which makes more sense. Jackson’s tribute to Louis takes up much of Side 1 with the rest of the side and all of Side 2 taken up by a good chunk of Armstrong’s old favorite, Satchmo: A Musical Autobiography.

The catalog page is probably the most interesting aspect of this entire tape. It crams the contents all onto a single side of paper but notice the second half: that’s not Louis Armstrong’s handwriting, but rather Lucille’s. What could the reason be? This is pure speculation but we’re probably in January 1971, a time when Louis performed in Las Vegas and complained to his doctor about shortness of breath. His health was slowly declining and perhaps back home from the exhausting Vegas trip, he asked Lucille to lend him a hand with his cataloging?

And here’s the back with Hal Jackson’s address at WLIB (reminder that Louis did all of his cataloging on the back of his “Lose Weight The Satchmo Way” diet charts!):

The confusion continues on the front of the box as Armstrong still lists “Von Blain + Family”–he must have had that portion of Reel 135 on his mind–and still lists “Al Jackson” instead of “Hal.”

Just a strip of tape with the reel info on the back:

Reel 162

Accession Number: 1987.3.460

Reel 162 opens with a repeat of Joe Delaney’s radio show from Las Vegas in September 1965, which featured an interview at the International Hotel interspersed with various Armstrong recordings. Remember, we shared that broadcast as part of Reel 130 here (and we shared the uncensored, unedited interview as part of Reel 132 here) so you can head to those links to listen. Here’s the catalog page for Side 1:

Side 2 opens up with something special: a radio broadcast of the All Stars live from Brandt Inn on Lake Ontario in Canada from c. January 1958 with Edmond Hall, Trummy Young, Billy Kyle, Mort Herbert, Barrett Deems, and Velma Middleton. Normally, this is when we’d share watermarked audio but that’s not necessary this time as this broadcast was licensed and issued on the Dot Time Armstrong album The Nightclubs, streaming everywhere and also available as a CD and LP (the Brandt Inn broadcast takes up tracks 11-16 on the CD, “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue” to “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South”). Armstrong follows with a dub of the 1956 Decca compilation Satchmo’s Collector’s Items, made up of some of his best Decca sides of the 1930s and early 1940s:

We’ve officially reached Christmas 1970 with the collages that make up the front and back of the box for Reel 162. The front features a holiday card sent by then-President of the United States Richard Nixon and his wife Pat; Armstrong cut out the center of it so it would fit on the box (you can see what an uncut version looks like here):

And on the back, a holiday card from All Stars clarinetist Joe Muranyi, featuring a photo of Joe’s son Paul playing trumpet. Muranyi spent his Christmas “break” playing the Tropicana Hotel with Armstrong so perhaps he gave his boss this card personally; he also wrote “Dec. 1970” on it in pencil, definitively dating it:

Reel 163

Accession Number: 1987.3.461

It might seem like a slow start to this post, at least as compared to some of our most recent epic outings, but that changes with Reel 163, another one of those tapes that found Armstrong pulling reels he originally made in the 1950s off his shelves and stitching them together to make a reel with a six-hour-plus running time!

This one opens with some unidentified operatic selections before Armstrong dubs the bulk of the Columbia Masterworks LP, Nelson Eddy In Songs of Stephen Foster. Next up is a Capitol LP from 1953 of the Ballet Theatre Orchestra conducted by Joseph Levine performing Chopin’s Les Sylphides, followed by another Capitol LP, this time of the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra conducted by William Steinberg doing Johann Strauss Jr.’s Waltzes/Polkas. After a few more tracks from the Nelson Eddy album, Armstrong turns to a recording of Verdi’s Il Travatore on the Cetra label, featuring the Radio Orchestra Italiana conducted by Fernando Previtali. Armstrong then dubs a version of his favorite opera, Cavalleria Rusticana, conducted by its composer, Pietro Mascagni and featuring Choir and Orchestra of La Scala in Milan. After a bit of Tito Schipa doing Don Giovanni from an RCA EP Schipa: Operatic Arias, Armstrong goes back to Nelson Eddy one more for the conclusion of that album.

After all the classical music and operas (and Nelson Eddy singing Stephen Foster), Armstrong turns back to jazz with a 1955 release by his one-time All Stars bassist Milt Hinton, East Coast Jazz. For some reason on the catalog pages, Armstrong drew black lines through his original cataloging of Hinton’s album in blue ink, but upon consulting the tape, the full album is there in full–here are the two catalog pages for Side 1 (the second page contains more cross-outs of Hinton selections that are on the tape):

Side 2 is where the gold is buried. First off is what Louis calls a “Big Special T.V. Broadcast – Early Days N. Y.,” which is really just Crescendo, a special DuPont Show of the Month that aired live on September 29, 1957 and featured Louis, Rex Harrison, Diahann Carroll, Dinah Washington, Benny Goodman, Stubby Kaye, Carole Channing, and more. Armstrong received a complete set of acetate records containing the audio of the entire 90-minute broadcast but this reel only features selections from those discs, though one is worth highlighting. 10 days before the broadcast, on September 19, 1957, Louis put his career on the line to speak out against the racial injustice going on in Little Rock, a story we told in this post. In the days that followed, Armstrong was slammed for what is no seen as the defining Civil Rights stand of his lifetime; there were boycotts of his records and his concerts and newspapers carried rumbles that DuPont no longer wanted him to appear on its “Show of the Month.”

Armstrong went on. One of his features was to play a chorus of “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen” on trumpet, seated in a rocking chair, immediately after Diahann Carroll sang it. Press agent Ernie Anderson remembered Armstrong preoccupied with something in rehearsal, searching for something to play on his trumpet and not quite finding it. But that night, during the live broadcast, Armstrong found it: in the middle of his solo on “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” he quoted “The Star Spangled Banner.” This country was letting down “his people.” Some of the newspaper coverage in the preceding days hinted that Armstrong was a millionaire and thus should have been disqualified from speaking but nobody knew the troubles Armstrong had seen and on national television, he made it crystal clear that that spiritual spoke for him, spoke for his race, and was more of an anthem than “The Star Spangled Banner” could ever be.

The next day, newspaper columnists and television critics praised Armstrong’s performance of “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Seen,” but in those pre-DVR days of live television, none of them picked up on the quote. Armstrong, however, wanted to make sure posterity wouldn’t forget what he had had done: when making this tape, he dubbed “Nobody Knows” once, then immediately rewound it and played it again, underlining the effect. Here’s the audio:

LAHM 1987.3.461

And if you’ve never seen Crescendo, it is now up on YouTube in its entirety; “Nobody Knows the Trouble I’ve Ever Seen” at 1 hour and 3 minutes in:

After that, Armstrong skips around a bit, sharing birthday greetings from Hugues Panassie and Madeleine Gautier of the Hot Club de France, as well as an unidentified friend from Montreal. The sound is really abysmal and isn’t worth sharing, but it’s a nice segment and also contains some music chosen by Panassie and the Montreal cat for the occasion: Louis’s “Potato Head Blues” and “Back O’Town Blues,” Lonnie Johnson’s “Blues in My Soul” and Ike Quebec’s “Blue Harlem.”

This is followed by audio of Russell Garcia and his orchestra performing an instrumental version of “Bess, Oh Where’s My Bess” from Porgy and Bess. Armstrong attempted to record this difficult number with Garcia in August 1957 but struggled, eventually running out of time (the struggles can be heard on the 4-CD set Cheek to Cheek: The Complete Duet Recordings, which is also streaming everywhere). Before the session ended, Garcia recorded the orchestra playing his instrumental and sent it to Louis to listen to while he was at home and on the road. Armstrong did just that–on another tape, he dubbed it about a dozen times in a row–and finally nailed the vocal when he returned to the studio on October 14, 1957. Thus, we’re definitely between September 29 and October 14 for this portion of the tape.

The part, though, is a bit of a mystery: it’s a very good interview with Armstrong in Switzerland on the show “Assignment Switzerland, Assignment the World,” which aired on the radio station Switzerland Calling out of Berne. The mystery is when was it conducted: it has the feel of a 1959 interview, and Armstrong did visit Switzerland that year, but it also has the same sounds of Louis in the background, coughing and at one point stopping the tape, that we’ve heard throughout the 1957 material. Thus, my gut is it’s actually Louis in 1957 dubbing an interview that took place in Switzerland in 1955 (he didn’t visit between 1955 and 1959). Either way, it’s a good one, allowing Armstrong to talk about his appeal to international audiences. He also tells some of his favorite stories, such as posing for pictures at La Scala, warming up in his dressing room with the “Intermezzo” from Cavelleria Rusticana, and the time Russian fans snuck over to Berlin to hear him play. Here’s the audio:

LAHM 1987.3.461

Armstrong then gets back in a classical mood, dubbing a recording of Grieg’s Holberg Suite, also most likely in 1957. But as we’ve seen on a lot of these tapes, after a long stretch of material originally recorded in 1957, Armstrong next spliced on a reel he originally recorded in 1951–and what a reel!

The fun begins with Armstrong in Los Angeles, which is where he began the year, performing at Club Oasis (it’s also where he bought his first tape recorder, at Music City in Los Angeles). Armstrong’s friend, the nightclub owner Stuff Crouch, a conspicuous voice on many of Armstrong’s earliest tapes, is also present. Armstrong opens by reading a poem sent to him by Mary Plummer that is entirely made up of the titles and lyrics of popular songs. Armstrong then plays part of a reel Crouch gave him of actress Margaret Starks doing a dramatic monologue. Armstrong mentions his European fan mail and asks Crouch to read a few. However, the phone rings and Crouch lets Armstrong get it, turning the tape off–and never turning it back on. Here’s the audio of that portion:

LAHM 1987.3.461

The very next voice on the tape is that of Armstrong’s–but he’s now back in Corona, alone in his Den, but telling an imaginary voice about how he and Crouch never did finish that tape. No matter, Armstrong is going to dub some records, opening with Bert Williams’s “When the Moon Shines on the Moonshine,” which Armstrong says he loved “as a kid in New Orleans”; that recording was made on December 1, 1919 and released in 1920 so Armstrong was 19-years-old (and married) but he still associated the song with his young days in New Orleans. Here’s the audio of Armstrong talking to us before and during the spinning of this record. We’ve let it run a little long as the sound of airplanes can be heard flying overhead from nearby Glenn Curtiss Airport (two years before being renamed after Fiorello LaGuardia) and Armstrong tells us to pay them no mind as there’s nothing he can do about it!

LAHM 1987.3.461

But after that comes a wonderful sequence where Armstrong takes us through the recording his “Laughin’ Louie” in 1933. Armstrong announces the song and says it’s by “Louis Satchmo Armstrong and His Orchestra and the guests who were around the studio that day–I put ’em all to work.” He then spun the entire 78, which we have included even though you can find it in better sound online (it’s also a bit sped up). At 3:30 Armstrong comes back on with a chuckle and “in rotation,” identifies the voices heard on the recording: Joe Lindsey, Armstrong’s boyhood pal from New Orleans, was up first, followed by trumpeter Ellis “Stumpy” Whitlock, someone named “Little Claude” I haven’t been able to properly identify, and Armstrong’s then-17-year-old adopted son Clarence Hatfield Armstrong (who shouts “Look out there, Pops!”).

Armstrong then talks about the “classical number” that he played at the end of the record, saying “it came from Erskine Tate’s Symphony Orchestra, when I used to play with them at the Vendome in Chicago in 1925. Now, to call the name of, I couldn’t call it because we had so much music to turn over and I didn’t pay much attention to the titles.” This stymied collectors for years; George Avakian asked Armstrong for the name of the tune during a recorded conversation in 1953 and Armstrong gave the same answer. In a footnote to the liner notes to a 1961 reissue of Armstrong’s Victor recordings, A Rare Batch of Satch, Avakian wrote about this number and said, “Please, if you know the title and source of this little gem, write me at RCA Victor!” It took about three decades but bandleader and multi-instrumentalist Vince Giordano finally solved the puzzle, identifying it as Minnie T. Wright’s “Love Song,” a theme Armstrong must have played countless times while accompanying silent movies with Tate’s Orchestra. (You can download a copy of the sheet music here if you’d like to play along.)

Then Armstrong plays “the other recording that gave us the idea of this silly thing,” “The OKeh Laughing Record.” Armstrong legitimately loved that 1920s novelty smash hit, owning multiple copies of the original 78 and dubbing it to a few tapes over the years. At 7:20, Armstrong says at the end of the record, “Now isn’t that the maddest thing you’ll ever want to hear,” laughing along himself. “That cat had me rolling, man!” The original 78 had a serious trumpet solo on the back of “The Gypsy Baron” so Armstrong sets that up, mentioning it was composed by Johann Strauss and he had just bought an album of Strauss’s waltzes. We’ve killed the audio clip at that point, but on the original tape, Armstrong dubbed that selection, then “Tomorrow Night,” which was the flip side of “Laughin’ Louie” and–treating the whole sequence almost like a radio broadcast–concluded with a dub of his theme song, “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South” from 1933. We’ve cut that out but here’s the priceless audio of Louis discussing and listening to “Laughin’ Louie” and “The OKeh Laughing Record”:

LAHM 1987.3.461

This tape continues gathering steam and finally hits a climax with a 30-minute conversation between Armstrong and his developmentally disabled adopted son Clarence. It’s actually such a special listen that we will actually save it for our next post, which will be entirely dedicated to the relationship between Louis and Clarence. You won’t want to miss it.

And even after that half-hour, Reel 163 isn’t finished! Armstrong goes back to classical with a recording of The Pines of Rome by Ottorino Respighi, conducted by Eugene Ormandy and broadcast on KGFJ radio in Los Angeles. Armstrong closes the tape a nice selection of jazz, blues, and popular music: “Neal’s Deal” (Count Basie), “You and Your Beautiful Eyes” (Dean Martin), “I Thought You Ought to Know” (Ivie Anderson), “Body and Soul” (Henry “Red” Allen), “Darktown Strutter’s Ball” (Red McKenzie), and “One and Two Blues” (Bessie Smith).

After all of that, here are the two pages describing that pretty incredible Side 2 of Reel 163:

The front of Reel 163 has a new collage from c. 1971, featuring a photo of “Claire and Bob” taken at the Grove in Los Angeles and sent to Louis. Claire definitely appears in some backstage photos taken during Louis’s 70th birthday celebration at the Shrine in Los Angeles, along with Floyd Levin, Barney Bigard, and others from the California hot jazz scene–does anyone know their last name?

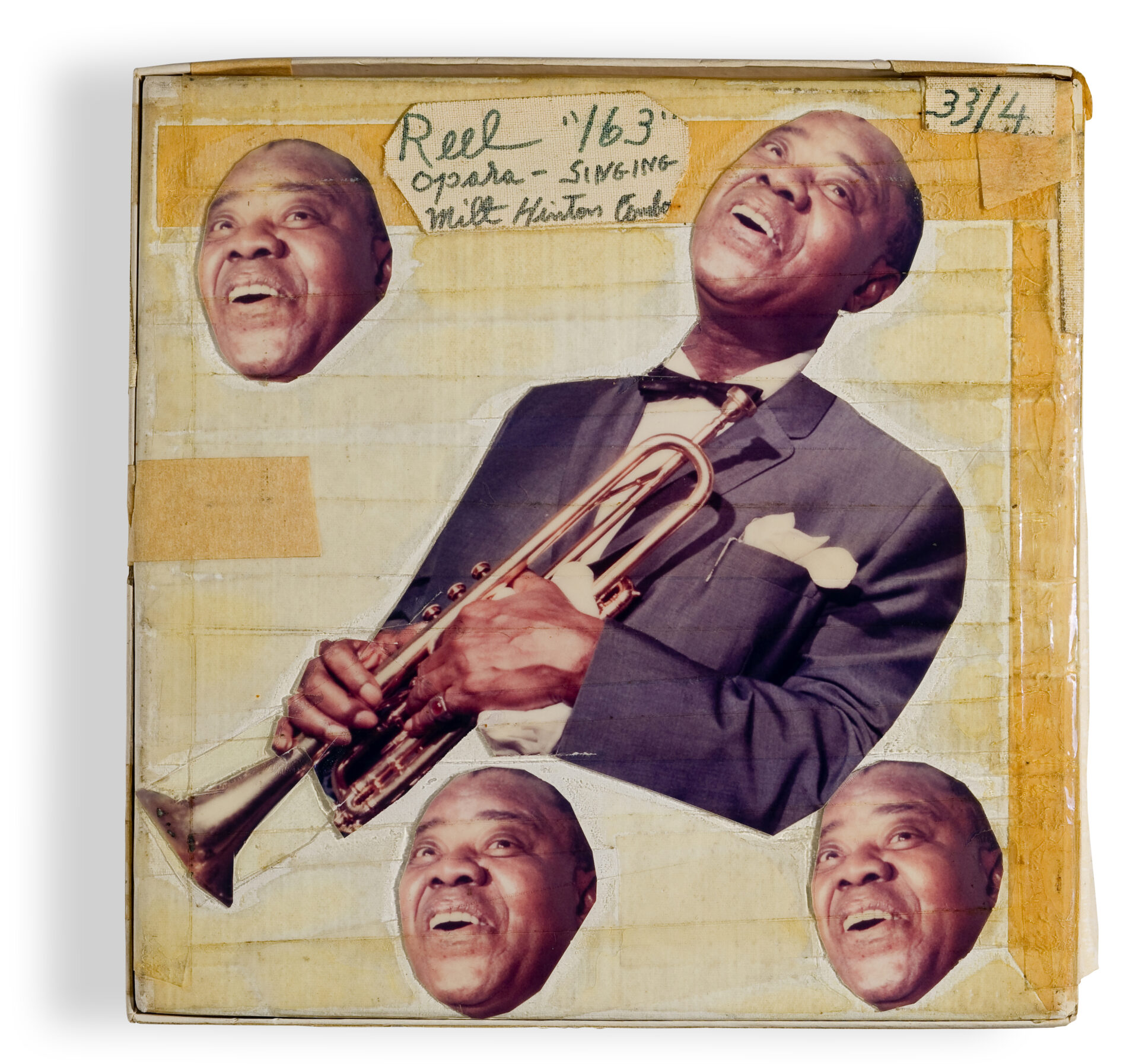

The back of Reel 163 is a class, an image that has been reproduced in coffee table books, in the Paris Review, and many other places as a prime example of Armstrong’s creativity as a collage artist. With four copies of the same 1960s color publicity photo lying around, Armstrong got out his scissors and tape and made a quartet of singing Satchmos!

Reel 164

Accession Number: 1987.3.462

Unfortunately, Reel 164 is one of those tapes where the sound quality is almost completely inaudible. Louis wrote “Jackie Gleason’s Choice Bands T. V. Show,” but it actually seems to be a dub of Gleason’s Stage Show, which was actually hosted by Tommy and Jimmy Dorsey. Eventually, Armstrong appears and the audio is taken from his August 21, 1954 appearance on Stage Show but is too distorted and quiet to share here…

….but good news! This series is devoted to Louis Armstrong’s reel-to-reel tapes but the Louis Armstrong House Museum is the world’s largest archives for any single jazz musician and contains 12 separate research collections in addition to Louis and Lucille’s stuff. We have mentioned the great Swedish Armstrong collector Gösta Hägglöf in multiple posts (and he’ll return later in this one); Hägglöf passed away in 2008 and in his will, left his entire Armstrong collection to the Armstrong House. Hägglöf traded tapes with another great collector, Bob Hilbert (we received Hilbert’s Armstrong records as a separate collection after he passed away) and Hilbert sent him a copy of the Stage Show broadcast in very good sound and that’s what we’re going to share now (watermarked as always for copyright protection).

This is actually a pretty historic broadcast. In our previous post, we shared audio of Louis and friends at home in Corona in January 1953. At one point, Louis cracks himself up telling a joke about a musician who asked for a tempo “not too slow, not too fast, just half-fast.” Little did anyone know that he put that joke in his pocket, waiting to spring it at the right time–which turned out to be on live television! After a beautiful version of “When It’s Sleepy Time Down South,” Louis talks with the Dorseys at 2:50 and drops the “half-fast” line–even without the visual, you can hear the reaction from the crowd! The buzz continues a few seconds into the number that follows, a rocking “South Rampart Street Parade,” a number rarely performed by Armstrong. Here’s the audio of the entire Stage Show sequence (and somewhere in an air conditioned vault must reside the video of this performance as Gleason was good at saving kinescopes of all of his shows and Elvis Presley’s famous appearance on Stage Show is easily available on YouTube; hopefully it becomes available one day!):

LAHM 2011.20.634

As a postscript, Armstrong’s line made headlines in many newspapers, some of which complained about its offcolor nature. Here’s one Louis himself saved for posterity:

And then for something completely different, we’re back in 1971 for a dub of Jerry Wallace’s huge hit (in Japan) “Mandom–Lovers of the World.” The song was originally used for a commercial Mandom, a male grooming product, and would star Charles Bronson, then hot from the film Once Upon a Time in the West. Jerry Wallace’s song was used in the commercial and became a huge hit–was Louis thinking of recording it or just keeping up with the trends? Here’s a YouTube video of it with the original commercial:

With that out of the way, here’s the catalog page for Reel 164 Side 1:

Side 2 continues on a Jerry Wallace kick with another dub of “Mandom,” this time repeated (I seriously think Louis was learning it), plus Wallace’s “With Pen In Hand,” “Primrose Lane,” and “Venus,” before another slice of 1970, “Nothing Succeeds Like Success” by Bill Deal and the Rhondels. There’s also a few poorly recorded traditional jazz numbers which sounds like they have vocals in Swedish in the style of Paul Whiteman’s Rhythm Boys; these might have been a gift of the aforementioned Gösta Hägglöf but I can’t say for certain (Louis just writes “Saturday Music,” which doesn’t help matters).

But the bulk of this side of Reel 164 is actually devoted to what would be the last new Louis Armstrong album released in his lifetime: Louis Armstrong’s Greatest Hits Recorded Live. We’ve discussed this before (namely in this post) but a brief summary is worth sharing again to set the scene. In July 1968, Louis and the All Stars did two televised concerts for the BBC, shortly before he ended up in intensive care. While convalescing the BBC sent Armstrong audio of the shows. Louis flipped, making copies for all the members of the All Stars, for friends, and dubbing them to tape (they appeared on Reels 25 and 27 of this series). Armstrong’s main goal was for his fans to hear the tape; he even wrote “For the Fans” on the outside of his copy of the tape the BBC sent him:

At some time, Armstrong’s wish came true: Brunswick Records agreed to release the highlights of the BBC shows, as selected by Armstrong himself; he even get his first “Produced by Louis Armstrong” credit for his trouble, which, according to Dan Morgenstern, he was very proud of. Here’s the front and back of the LP (which sadly is not streaming):

It’s often stated that Louis “County and Western” Armstrong was Armstrong’s final album, which is true in that it features the last music he recorded in the studio. And “The Night Before Christmas,” recorded at home on February 26, 1971 (more on that next week) was technically Armstrong’s final commercial recording, even though it was released posthumously. But though the material was a few years old, it’s quite satisfying that Louis Armstrong’s Greatest Hits Recorded Live was the final new Armstrong album released before he passed away: it’s got many of his biggest hits of the last 25 years of his career, it was produced by him, it featured much excellent trumpet playing, and he truly wanted his fans to hear it so badly. It’s a very fitting punctuation mark on Louis Armstrong’s recording career.

Here’s the catalog page for Side 2 of Reel 164:

British jazz and blues vocalist Beryl Bryden adorns the front of the box for Reel 164:

Bryden visited the Armstrongs in Corona in the summer of 1970 and took some photos, most of which Louis put in this scrapbook. This also looks like her work, a charming photo of Louis in his Den posing in front of one of his Tandberg tape decks:

Reel 165

Accession Number: 1987.3.463

I’ve been hinting that we’re in early 1971 for a while but now it’s confirmed with Reel 165 opening with a recording of The Pearl Bailey Show that aired on January 23 of that year. This was Bailey’s first episode of an ABC variety show that sadly only lasted four months. She brought out the big guns for her premiere, getting Bing Crosby and Andy Williams in addition to Armstrong. Armstrong signed his contact on October 30, 1970 and spent November 2-5 rehearsing and taping the broadcast. He was probably exhausted having just returned from a performance in London, his final trip overseas and one where his chops deserted him at the performance. Armstrong played trumpet every night during his International Hotel run with Bailey back in September, but he left his horn at home for the taping of this show.

We’re going to share the audio of the entire episode, but here’s what to expect. Bailey opens with “Applause, Applause” and, after some commercials, does a monologue. Bing then comes out and “Bridge Over Troubled Waters” before singing a medley with Bailey. Bailey reminds the audience of her background as a dancer, launching into a routine set to the song “Chicago”; we can’t see it but the band, led by Bailey’s husband, drummer Louie Bellson, positively cooks (can anyone identify the swinging, two-fisted pianist?).

At 25:36 Pearl introduces Louis and they talk a bit, reprising their nightly repartee from the Vegas run. Armstrong does “Blueberry Hill” and then teams with Bailey for a hot version of “Exactly Like You” (Armstrong’s trombonist Tyree Glenn can be heard loud and clear in the background). Bailey sounds like she’s trying to swallow him whole, but Armstrong holds his own and grabs the last note, saying he had it in his pocket the entire time. Bailey is confused and thinks Armstrong is talking about his mouthpiece. Armstrong sounds like he wants to prove that he can blow the trumpet but Bailey abruptly gets him off it by beginning a touching rendition of Jimmy Webb’s “Didn’t We,” Bailey singing the lead and Armstrong mostly humming and scatting some harmonies behind her. (This tape had an audio issue and cut off half the performance; I edited a complete version from another copy of the broadcast Armstrong had, but the sound still has some issues.) Video of this duet hasn’t been made public, but here’s a nice Getty photo of the moment:

Andy Williams is up next, doing “I Who Have Nothing” and duetting with Bailey on “Give Me the Simple Life.” Then comes a cute bit of special material at 44:36, “I Don’t Want to Sing That Song,” which features the three special guest singing about how sick they are of their signature tunes–leading the others to perform those very songs. Armstrong and Williams do “When the Blue of the Night” for Bing, Armstrong and Crosby do “Moon River” for Williams and Crosby and Wiliams do “Mack the Knife” for Louis. Bailey finally joins them and they all team up for “Hello, Dolly!” as Bailey was associated with a popular iteration of the long running musical (no one references Louis’s own connection to that song!), with a brief interpolation of “Bill Bailey.”

But now, some good news! A copy of the complete broadcast exists in Bing Crosby’s Archives and the good folks who run it have posted this medley on YouTube. Louis looks tired at times and even thinner somehow since his summer appearances, plus it’s clear that he doesn’t know the special material as well as Williams and Crosby (he jokes “Let me struggle with it” before his section), but he still flashes the old spark at times, singing Crosby’s theme song quite beautifully. Armstrong’s struggles with phlebitis were becoming more pronounced but he still does his best to do those leg kicks at the end, though he needs some assistance getting down the one step off the stage–what a trooper:

On the audio track, Bailey comes back on after a commercial and performs, “Mama, A Rainbow,” says goodnight, and closes with “I Love You.” Until the full video is available, here’s the watermarked audio of the entire episode:

LAHM 1987.3.463

Side 1 ends with a curiosity. The big motion picture hit of 1970 was Love Story, which featured the iconic quote “Love means never having to say you’re sorry.” It’s not a surprise that someone soon wrote a song with that title but it might be a surprise that a demo of the song ended up at Louis Armstrong’s home. Like “Mandom,” Armstrong repeated it twice at the end of the reel–perhaps he was thinking of recording this one, too. Here’s the catalog page:

The bulk of Side 2 of Reel 165 is actually a copy of a side of Reel 49, which we discussed here. I usually don’t do this, but I think it’s worth repeating my original description of this material:

Reel 49 is another 1970 compilation but it’s a real hodge-podge that it seems was made with an eye towards Louis’s return to the stage; more on that in a minute. The reel opens with “You’re in New Orleans,” a demo of a song written by his friend “Creole Charlie,” real name Charles Levy (potentially the same Charles Levy who composed “35th Street Blues” for Jelly Roll Morton in 1924). This is followed by four of Armstrong’s solo features from his 1957 collaboration with Ella Fitzgerald on Porgy and Bess and his recording of “That’s For Me” with the All Stars in 1950. Then “Creole Charlie” takes over for a bunch of demos of his compositions before Louis ends the reel with “I Surrender Dear” from the same 1950 date as “That’s For Me” and one his Italian sides from 1967, “Dimmi, Dimmi, Dimmi.” Not much more is known about “Creole Charlie” but he did apparently co-write a song with Louis based on his laxative-inspired advice, “Leave It All Behind You.” Armstrong wrote to Levy on July 18, 1970 to say he was going to record it, along with “You’re in New Orleans,” and he told the same thing to Max Jones in a letter from August 15, 1970, but alas, the recordings never came to pass.

In my original post, I mentioned that Armstrong wrote the lyrics down of every song on the reel. Perhaps he did it when he originally created it in 1969-1970–or perhaps he did it now in 1971. To cover all bases, here are the handwritten lyric pages again (with some extra ones we skipped in 2020; this is the complete set):

That concludes the repeat of the material of Reel 49, but with a little bit of time, Armstrong dubbed “Love is Never Having to Say Your Sorry” again…then “Mandom” again…then Neil Diamond’s “He Ain’t Heavy, He’s My Brother,” which was released on November 5, 1970. If Armstrong had lived longer and made another album, it might have been a strange one! He at least closes the reel with two of his own recordings, “Mame” and “I Get Ideas,” the latter of which was left out of the catalog page:

The July 4, 1970 issue of the Swedish newspaper Svenska Dagbladet had a feature on Louis’s 70th birthday that was sent to him by Gösta Hägglöf. Here’s what it looked like intact, from our Gösta Hägglöf Collection:

Armstrong now went to work, cutting the photos out from the newspaper in order to make the collages that adorn the front and back of Reel 165. Here’s the front:

And here’s the back, which features a photo of Hägglöf himself, which sadly I don’t believe he was ever aware of:

One wonders if Hägglöf sent Armstrong the Swedish newspaper at the same time he sent him some albums that he produced. Armstrong wrote to Hägglöf on February 10, 1971 to thank him, which is right in line with where we’re most likely at with Reel 165:

But to go back to the Swedish newspaper, you might notice the only photo missing from the above collages is the one of Louis with King Oliver, which he used on what might be the next-to-last tape he ever made before he passed away (shared and discussed in this post from 2021). I’ve been speculating we’re in February 1971 given the contents of this tape but if Louis already used the Swedish newspaper to make this collage and the Oliver collage at the same time, it’s possible we’re actually much closer to July 6, 1971 than I imagined, at least regarding the collages. There’ll be some detective work and open questions in the upcoming installments of this series, but before we get too morbid, come back soon to hear the tape of Louis and Clarence Armstrong from happier times.