Louis Armstrong’s 1969-1971 Tapes: Reels 91-95

The last few installments of this ongoing series have been particularly action-packed, with lots of strong collages and audio samples from the tapes. A good example is our post on Reels 86-90 which had collages featuring Joe Glaser and the Pope (not together) and audio of Louis on both The Tonight Show and The David Frost Show. And Reel 87 was so loaded with good conversation, it inspired our first-ever entry on a single tape. Of course, not every installment can be so exciting and today is a transitional post of sorts, with some repeated content and a lack of collages. Still, we do have some unique audio once again and for those who have been following along, it should hopefully provide more insight into how Armstrong spent his free time in the spring of 1970 (and there’ll be a bonus for New York Mets fans, as hinted it by the image at the top of the page). Let’s dive in:

Reel 91

Accession Number: 1987.3.391

We actually begin with a truly heart-warming story (plug alert: this story makes up a big part of the Epilogue to my 2020 book Heart Full of Rhythm). Zutty Singleton was not only a pioneer of jazz drumming but he was one of Louis Armstrong’s closest friends in New Orleans and Chicago, the two eventually immortalizing their musical partnership with a series of timeless recordings in 1928 and 1929. But at the end of 1929, Armstrong’s band was fired from Connie’s Inn in Harlem and Singleton immediately took another job with Ally Ross’s band–that began the very next night at the very same venue. Singleton explained to Armstrong, “Well, Louis, business is one thing and friendship is another,” but Armstrong was wounded. Their friendship was downgraded to the level of almost acquaintances, the pair only musically reuniting for sessions in 1940 and 1946. After Mezz Mezzrow told the story of Armstrong and Singleton’s breakup in his book Really the Blues, the old wound came flaring back and Armstrong became disgusted with Singleton, cursing him out as “a selfish man” to friends on his private tapes and insisting to Joe Glaser that he never, ever hire Singleton to join the All Stars. By the 1960s, the two old friends no longer spoke.

But then Louis’s health took a turn for the worse with his two stints in intensive care in 1968 and 1969, rendering him more or less retired. And in late December 1969, Zutty suffered a debilitating stroke and would never play drums again. When word of Singleton’s condition reached Armstrong, he knew it was time to bury the hatchet. Zutty’s wife, Marge, remembered, “Now when Zutty got sick, Louis came here and everything and was carrying on something awful and told me, ‘Marge, I believe if Zutty would die, I think I’d kill myself.’” Louis visited Zutty in his apartment at the Alvin Hotel and noticed a 1929 publicity photo he had originally signed, “May we never part.” Well,” Armstrong said, “we picking up from where we left off!” Marge Singleton added, “And the way he bathed Zutty and wheeled him out to the house like Zutty was a piece of gold. And tried to shave him, tried to do everything. Because he knew Zutty loved him and he loved Zutty.”

This touching story is the preamble to Reel 91, which opens with a dub of Singleton’s very last recordings, made with a group featuring Johnny Wiggs (cornet), Ernie Carson (2nd cornet), Bobby Gordon (clarinet), Bob Greene (piano), Danny Barker (guitar), and Van Perry (bass), at the Manassas Jazz Festival on December 7, 1969, just before his stroke. Thanks to YouTube user “Davey Tough” for uploading “Bourbon Street Parade,” which opens Reel 91:

After opening with Singleton’s final recordings–given to Armstrong, presumably, by Singleton himself–Armstrong then went into repeat mode, copying material from other tapes he had already made. In this case, the rest of Reel 91 is almost an exact copy of what we discussed (and shared audio from) of Reel 70, which opened with coverage of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s assassination and funeral (sent to Louis by Tony Janak) on Side 1 and then more of the funeral, “Hello, Dolly!” with Barbra Streisand, and scattered V-Disc recordings of Fats Waller, Art Tatum, Hot Lips Page and others on Side 2. The second side, though, does end with four Armstrong sides made between 1929 and 1932, including “Black and Blue,” where Louis lets us know that “ZUTTY” is on drums–perhaps he was making a copy of this tape for his old friend? (It’s also worth pointing out that Reel 70 had audio of Armstrong’s full January 1970 appearance on The Dick Cavett Show, where he sounded shaky on trumpet; for this dub, he cut all of that out and only included the duet with Streisand.)

Yet more speculation: producer Bob Thiele remembered visiting Louis at home in Corona sometime in March 1970 to begin discussing what would become the album Louis Armstrong and His Friends. We’ll have more to post on that visit in the near future, but Thiele recalled that when he suggested Armstrong record “We Shall Overcome,” “Louis’ eyes lit up. He reached up and pulled down a tape of the Martin Luther King funeral that he’d made. We played it and he said he loved the way the choir sang the piece during the service.” So perhaps this dub was made during Thiele’s visit and after a visit to Singleton’s home. Either way, here’s the catalog pages:

This is a sad post in that it features zero collages. Armstrong had a string of plain black tape boxes and just used them to get his catalog numbers on, something he continued for a while (but don’t worry, the collages will return in the future!). Thus, to get it out of the way and to avoid repetition, we’ll be sharing all the scans of the front and backs of each box, but I won’t have much to say about them.

Reel 92

Accession Number 1987.3.392

Reel 92 picks up where Reel 91 left off, with dubs of five classics Armstrong originally recorded with Zilner Randolph’s group in November 1931 (not the “All Stars” as he notes). But then he reached back for something we already discussed way back when, a 1952 tribute to Armstrong that already appeared in this series as part of Reel 7. It was originally part of Armstrong’s 1950s tapes that occasionally got re-catalogued and here it is again–but this time we’re sharing the audio!

The recording is of an All-College Conference on the Arts in America dinner honoring and hosted by George Wein, the first voice in this clip (Wein passed away one year ago this week). After Wein makes opening remarks, he introduces Nat Hentoff, who talks about a Downbeat Hall of Fame recently award given to Louis and thanks Louis for “All the kicks.” Then the highlight: Louis gets to the microphone and reminisces about an incident that recently happened in New Orleans, when the intermission of the All Stars’ concert featured the unveiling of a large photograph of clarinetist Leon Roppolo. At that concert, Myra Menville of the New Orleans Jazz Club gave Louis the microphone–and Louis told one of his favorite dirty jokes, the “hamburger” story (also told by Redd Foxx). So what does Armstrong do in Boston? Tells the very same joke!

It brings down the house and then it’s up to Wein to restore order and introduce speeches by Chairman of the New England All College Conference, Richard T. Watson of Harvard University, and Jim Randall of Boston University. A tape is then played of Tallulah Bankhead congratulating Louis, and reading a quote from an article she wrote for Ebony Magazine. Watson then presents a scroll to Louis, who makes a speech and thanks everyone. Apparently, Armstrong performed “Struttin’ with Some Barbecue” at that point but perhaps it wasn’t recorded because at that moment, he used some audio trickery to insert a live All Stars version of “Barbecue” from Copenhagen in September 1952.

Apologies for the long description but here’s the audio (“Barbecue” isn’t in good quality but we still included the first two choruses for the die-hards out there):

After that, Armstrong continued to reach back for a backstage conversation he taped at the Chicago Theater in 1953 that originally made up the entirety of Reel 11 in this series. For that one, Armstrong just took the original tape and box and stuck a new “Reel 11” sticker on it but here he dubbed it (in slower speed, 3 3/4 as opposed to the original 7 1/2) to round one one extremely long Side 1. (And in our original description from 2020, we said this tape was “unsuitable for children” and we stand by that so there won’t be any audio shared from that but Louis’s handwritten description of “Lots of Laughs” is apt!)

Side 2 is all fresh material, opening with Mary Lou Williams’s brand new LP (released in 1970 on her own “Mary Records” label), Music for Peace. Notice Armstrong really take his time with his handwriting to denote each movement; almost looks like the penmanship of a different person at times but he was clearly taking his time to get it all right. (You can listen to the complete album on YouTube here.)

Next up, something completely different: The Miracle Mets, an LP that commemorated the New York Mets’s world championship season of 1969. Armstrong was a Mets fan and occasionally visited Shea Stadium, located just a few minutes away. In fact, he was at the clinching Game 5 of the 1969 World Series, interviewed between innings by Tony Kubek, as seen here (at the 1:38:10) mark:

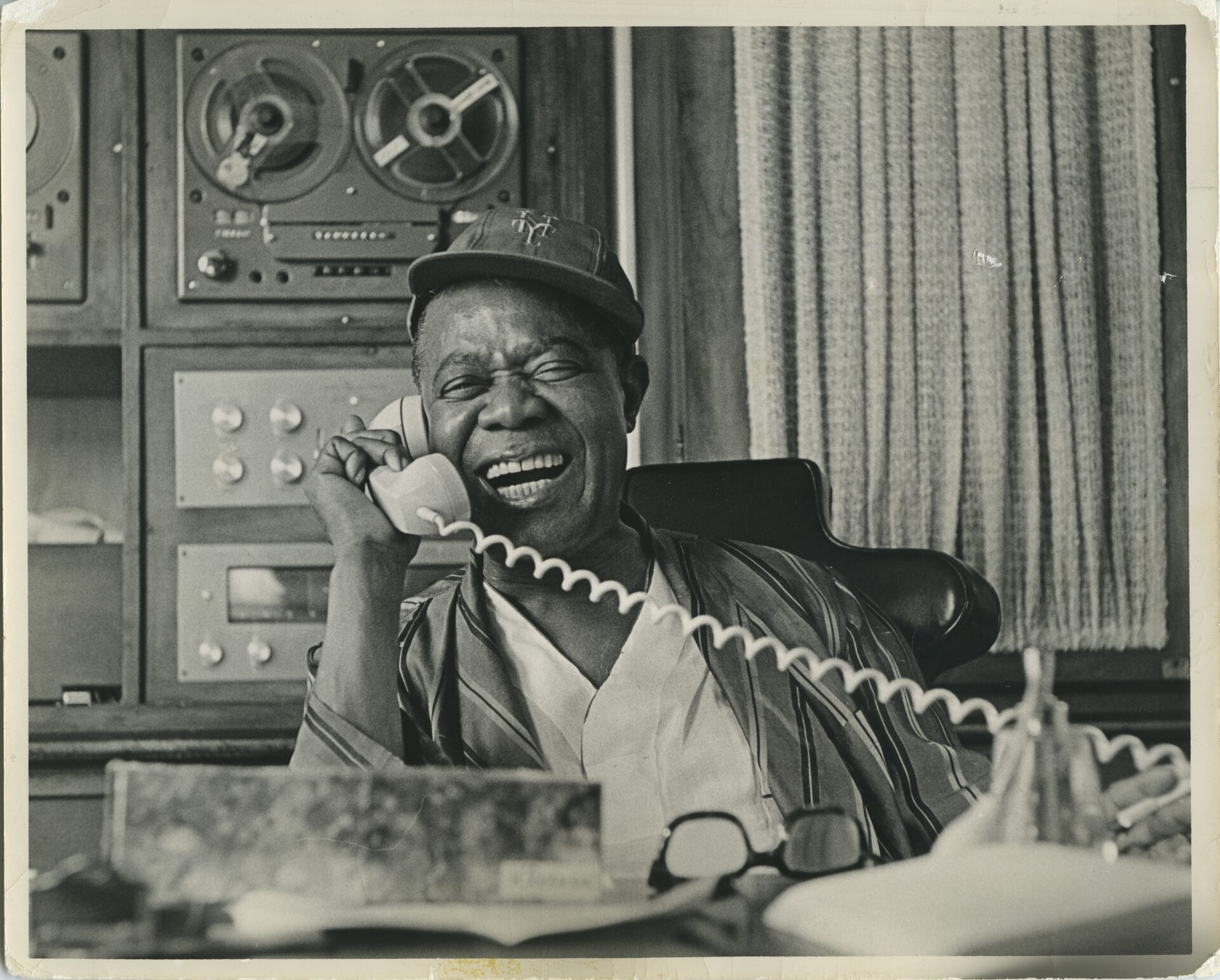

Jack Bradley visited Louis around this time and took this now iconic image of Armstrong on the phone in his den, proudly wearing a Mets cap (when the photo first appeared in the July issue of Downbeat, the caption simply identified it as “Spring 1970,” which seems right in line with the March-April time frame for when I’m assuming these tapes were made):

(Did you know that after Louis died, Lucille said one of his only regrets was the Mets never asked him to play the National Anthem at Shea. We have recordings of him playing it–come on, Mets, let’s rectify that!)

For whatever reason, Louis only dubbed Side 1 of The Miracle Mets, though he remembered to update the listing to notate that the rest is on Reel 115, which we’ll get to in due time. (For those who would like to listen to the full original LP, it, too, is on YouTube here.)

Finally, Armstrong finishes off Reel 92 with the first part of another brand new album, Dizzy Gillespie’s The Real Thing, recorded in 1969 and also released in early 1970 (and also available in full on YouTube here). Interesting to see Armstrong still following the challenging sounds being made by Williams and Gillespie, two old friends (who also probably gave Armstrong these copies of their records; Gillespie was still living around the corner in Corona and our Archives has multiple gifts from Williams, including an inscribed Bible).

Here’s the box for Reel 92:

Reel 93

Accession Number: 1987.3.393

Reel 93 follows the pattern of Reel 92, opening with another dub of a conversation originally recorded in Boston in the early 1950s that already appeared in full back on Reel 15. This particular conversation is another wild and wooly one that’s not appropriate to share at the current time, but it’s also difficult to hear as Louis and guests–Trummy Young, Velma Middleton, and the Jones Brothers–talk while spinning records the entire time (note that it’s Benny Goodman and Charlie Christian’s “Rose Room,” not “Pool Room” as notated below!)

With that out of the way, it was time for Armstrong to revisit three of the most oft-dubbed records of this series: Ambassador Satch, Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy, and Satchmo the Great (note that Side 2 of The Miracle Mets must have appeared on this tape at one point but perhaps it got erased by accident as Louis crossed it out and didn’t finish it until Reel 115):

Reel 94

Accession Number: 1987.3.94

I felt a sense of deja vu creeping in when looking at Reel 94, and with good reason: Armstrong was now copying material that he had already done on Reels 82 and 83 (described here). He even follows the same order of Reel 82, opening with the conclusion of Satchmo the Great, side 1 of Louis Armstrong Favorites, then complete dubs of the first two volumes of Columbia’s Louis Armstrong Story series dedicated to “The Hot Five” and “The Hot Seven,” before closing with the beginning of The Real Ambassadors.

Like the tapes in the 80s series, Armstrong didn’t have the original LPs at hand because his cataloging is all over the place as he valiantly tried remembering the titles of songs he recorded over 40 years earlier. He also had trouble with names; once again, Joe Sullivan is mixed up with Frank Signorelli on “Knockin’ a Jug,” resulting in the humorous mashup “Joe Sigmarelli”! (Good stage name…) He once again points out any and all contributions by Zutty Singleton, even on sides where Zutty wasn’t present (Baby Dodds is on the Hot Seven numbers but that doesn’t stop Armstrong from identifying Zutty on “Gully Low Blues” and “Melancholy Blues” on Side 2).

We also get a note about trombonist John Thomas’s day job as he’s identified as “John Thomas the Undertaker” on Side 2! Armstrong really struggled with the Hot Seven tune titles but the ones he came up with below are almost more interesting. The original LP (and we double-checked the order on the original tape) opens with “Potato Head Blues,” “Wild Man Blues,” and “S. O. L. Blues.” But as seen below, Armstrong called them “Don’t Jive Me” (title of a later 1928 recording), “Blues for Hines-Armstrong” (though Hines isn’t on this track) and most fascinating, “Blues for Bix.” Following the order below, “Blues for Bix” is how Armstrong remembered “S. O. L. Blues” but the order is so hard to follows, one wonders if he meant that for “Potato Head Blues” and it’s famous, lyrical stop-time chorus.

Armstrong gets the next several titles right, but he didn’t remember “Willie the Weeper,” “Alligator Crawl,” “Keyhole Blues,” or “Chicago Breakdown,” though he did correctly remember the sound of Stump Evans’s tenor (referred to as “Stomp” Evans) and Hines’s piano on the latter.

The Real Ambassadors finishes out Reel 94 though as he did on Reels 82 and 83, he recalled Yolande Bavan as the vocalist, though it’s Annie Ross on the recording (Bavan took part in the only live stage of this work and must have left an impression):

There is one interesting thing to point out in the otherwise blank box that houses Reel 94: it originally contained a note from engineer Tony Janak listing Louis and Duke Ellington’s appearances on The Dick Cavett Show. Once again, we’ve already shared audio of both of those, as they wound up on earlier Louis “mix tapes,” Ellington appearing on Reel 84 and Armstrong’s appearance on multiple tapes, including Reel 70. Surely, there was a method to his madness, but even after all this analysis, I can’t always crack the code!

Reel 95

Accession Number: 1987.3.395

Reel 95 is an exact duplicate of what we’ve already discussed on Side 1 of Reel 83 opening with the conclusion of The Real Ambassadors, then dubs of The Bessie Smith Story Volume 1, The Louis Armstrong Story Volume 3: Louis and Earl Hines, and side 2 of Louis Armstrong Favorites. Again, the cataloging has some interesting tidbits; Armstrong hears Smith’s “J. C. Holmes Blues” as “Casey Holmes” (closer than Reel 83, which described it as “Casey Jones”). The catalog entry for Side 2 has a rare “edit,” with Armstrong sticking a piece of tape on the page to correctly identify the title of “Jailhouse Blues.” Of the Hines sides, Armstrong didn’t remember the titles of “No (Papa, No)” and “Muggles,” simply, but accurately describing them as “Blues Hines Satch,” while “Skip the Gutter” becomes “Jump Blues.” Finally, note that after “Lazy River,” Armstrong writes “SECRET NINES,” a reference to the baseball team he sponsored in New Orleans in the summer of 1931, a few months before he recorded “Lazy River.” Clearly, his brain connected the two events but I suppose we’ll never know why.

That concludes this look at Reels 91-95, a bit meatier than I originally envisioned (and speaking of meat, don’t miss the audio of that hamburger joke!). We’ll be back next week with Reels 96-100, an entry that will include a lot of audio of Armstrong’s talk show appearances of early 1970.