“The Great Chicago Concert”: 65th Anniversary Celebration

This is a bit of a departure from our “That’s My Home” theme, which admittedly has taken us out of Queens more often than not lately. But when dealing with the globe-trotting life of Louis Armstrong, it’s awfully hard to keep him pinned down to one location!

Thus, today’s post will celebrate what was another one-nighter during an incredibly busy period in Louis Armstrong’s career, a benefit for Multiple Sclerosis held at Medinah Temple in Chicago on June 1, 1956. Armstrong played countless one-nighters in this period (and throughout his career) but this one had a few extra things going for it: it co-starred actress Helen Hayes reading a script about “50 Years of Jazz,” there were costumes and sets, and even a dancing troupe. But most importantly, the contents of the evening were being recorded by George Avakian for Columbia Records.

As discussed in our recent post on the album Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy, Avakian smartly wooed Armstrong and Joe Glaser over to Columbia when their Decca contract was up and put out three killer releases in a row, Handy, Satch Plays Fats, and the single “Mack the Knife,” and had just finished recording the music for what would become another popular release in April 1956, Ambassador Satch. Here’s Louis’s copy:

Avakian had proved himself to Glaser, making Columbia the preferred label of choice for Armstrong in Glaser’s eyes. Thus, when Glaser was contacted about a potential benefit concert that would feature Armstrong and Helen Hayes for one night in Chicago, Glaser immediately pitched it to Avakian as a potential evening that should be recorded.

How do we know this? Here’s the backstory to the backstory: sometime in the 1970s or early 1980, Columbia Records was downsizing its office files, preparing to discard any files that no longer seemed important. Chris Albertson was working for Columbia at the time and noticed that a hefty file with the words “Louis Armstrong” was sitting out in the open. He inquired about it and was told that it was about to be thrown out. Albertson realized this was too important for the trash heap so he took the file home with him. It contained all of the interoffice memos at Columbia during Armstrong’s 1954-1956 run with the label, copious correspondence with Glaser, all of Avakian’s handwritten edit notes for Handy and much of Ambassador Satch and much more. In 2016, the Louis Armstrong House Museum purchased the folder directly from Albertson himself (he passed away in 2019). Thus, we are able to present the complete backstory as its never appeared before.

According to a post-concert column by Herb Lyon in the Chicago Tribune, “Seems Johnny Baker, a key man in the midwest’s multiple sclerosis fund raising efforts, knew only two show business names personally–Helen [Hayes] and Satchmo. He appealed to them and both said yup pronto.” We don’t have anything from that original negotiation–it’s said in another article that Glaser had to cancel a previously booked Armstrong performance to make him available for June 1–but the Columbia file does include a February 21, 1956 letter from Michael Cudahy of the Chicago Chapter of the National Multiple Sclerosis Society about the idea of recording the show:

That was enough for Glaser to forward the letter to Avakian, telling him he thought it would be “sensational” for Columbia to record the show:

Avakian did not share Glaser’s enthusiasm. While recording Ambassador Satch, Avakian recorded a complete All Stars show at the Concertgebouw in Amsterdam. It was a great concert, but included much of the same repertoire covered on live Decca releases such as Satchmo at Symphony Hall, Satchmo at Pasadena and At the Crescendo. Not only that, but Decca had an ironclad clause that no other label could release Armstrong performances of the same songs Decca recorded until five years had passed.

Avakian got around this by setting up a recording session in an empty theater in Milan in December 1955. The All Stars brought an entourage of noisy Italian friends and fans and recorded different material until 5 o’clock in the morning, including “The Faithful Hussar,” “West End Blues,” “Tiger Rag” and others. To finish the deal, Avakian recorded the All Stars in the studio in Los Angeles in January 1956 to wax “All of Me” and “Twelfth Street Rag,” finishing off the album.

Avakian produced another masterpiece but was scarred from the experience and told his boss at Columbia J. B. Conkling that recording another live All Stars show would basically be pointless without insisting that Armstrong record fresh repertoire:

On March 14, 1956, Avakian finally responded to Glaser, sharing his hesitations: he wasn’t entirely sold on what Hayes would bring to the table, she would have to share royalties with Louis, and “Louis’ regular repertoire must be overhauled because at this point there are hardly half a dozen tunes which he performs in his shows which are also available for recording:

Glaser replied on March 20 that he agreed wholeheartedly with Avakian, writing “if a deal can be worked out, I will see that Louis played many different tunes as he has many, many numbers in his repertoire–unless you have some specific numbers in mind for him to do….”

Avakian still wasn’t sold but he had to play ball with Glaser because Columbia was also hard at work negotiating an exclusive ten-year contract to sign with Armstrong and they wanted to stay on Glaser’s good side (Avakian’s impersonations of Glaser in this Columbia interoffice memo are quite funny and telling).

With that, the concert was set and Columbia was on board to record it. Jack Tracy of Downbeat magazine was hired to write the script, using a theme of “50 Years of Jazz.” He was an interesting choice as he was not one of Armstrong’s biggest fans and was just weeks away from causing a stir with his over-the-top vicious review of Armstrong’s set at the Newport Jazz Festival just a few weeks after the Chicago concert. He also must have thought it was restricting doing a “50 Years of Jazz” show with only one band that didn’t play in any of the more “modern” jazz styles. He submitted his script with a shrugging note:

Avakian approved, though he made some handwritten edits to his copy. By mid-May Avakian was consumed with Armstrong’s overseas exploits as he would go from Australia in April to the United Kingdom for much of May. Edward R. Murrow and Fred Friendly of CBS were following him and filming him for the eventual documentary Satchmo the Great and Murrow convinced Glaser to shoehorn in a three-day trip to the Gold Coast of Africa in late May. Avakian was keeping tabs of what was being recorded for the film as he knew the eventual soundtrack would fall on him to produce.

On May 11, he checked in with Glaser and gave further thoughts on the upcoming Chicago concert. Tracy’s script had broken everything into four segments so Avakian suggested numbers for each one, as related in the following letter:

As can be seen, that letter only survives on a slightly blurred photocopy. If you can’t read it, here’s a transcription of the relevant portions:

Dear Joe:

Mr. R. W. (Bob) Ferguson, vice president of Wherry, Baker & Tilden in Chicago, phoned me at your suggestion to discuss the Helen Hayes-Louis Armstrong concert June 1 at the Medina Temple in Chicago.

I told him that I had read the Jack Tracy script carefully, and it was very good, but I was still in doubt as to the wisdom of having a recording with a narrator, even though Helen Hayes in unquestionably a very fine person to have as a narrator. I said it would be hard to judge whether the idea was good or not unless one actually tried it. At which point he suggested something which I am quite willing to do: that the program be recorded on speculation, and we decide afterward if we want to issue it.

Helen Hayes and the Multiple Sclerosis Society do not want any payment or royalty for the recording. The speculative recording can be made in this way, if it is satisfactory to you: we will pay Louis and the men union scale for one session whether we use the recordings or not, and if we use them we will then add Louis’ regular fee and double the scale for the men for as many sides as we end up using. We will carry the entire risk of engineering cost, which is considerable.

Frankly, I see very little risk in this for all concerned because even if the idea of using the concert with Helen Hayes’ narration does not work out, we will at the very least get 3 or 4 fine performances from the band which we will use somehow. Therefore I am confident that it is worth our trying, and that Louis and the men will get some good money above the minimum of one session.

As for repertoire which will fit in with the script and be available to us, free of Decca restrictions, that is something of a problem, but I think this is the best solution. It may involve Louis’ dusting off some tunes he hasn’t played for some time, but I am sure he can do it. The tunes are grouped according to Miss Hayes’ text:

New Orleans:

HIGH SOCIETY

SLOW FUNERAL PARADE MUSIC (suggest JUST A CLOSER WALK WITH THEE)

FAST FUNERAL MUSIC (suggest OH DIDN’T HE RAMBLE)

Riverboat:

PANAMA

FRANKIE AND JOHNNIE

RIVERBOAT SHUFFLE

NEARER MY GOD TO THEE (procession out of Storyville)

Chicago:

DIPPERMOUTH BLUES

THAT’S A PLENTY

WILD MAN BLUES

POTATO HEAD BLUES

New York:

MANDY, MAKE YOUR MIND UP

BABY WON’T YOU PLEASE COME HOME

EVERYBODY LOVES MY BABY

Finale: Any set of tunes Louis wants to play. The material above would be enough for our album, and actually I would switch some of the Riverboat, Chicago, and New York songs to form our own finale.

In this way, Louis has total freedom to perform what he wants at the end of the concert itself, regardless of Decca restrictions, and we will be able to re-arrange the program to suit our requirements for the album.

I am sure that Oscar Cohen can get copies of the music where needed, but if you have any problems in that line please call my secretary and she will help you. I will be away from May 15 to 22, but everyone who has to be notified about this will be ready to cooperate 100%.

Please let me know if this idea seems OK, and we can go ahead accordingly.

Best regards,

George Avakian

*************************

It’s easy to admire Avakian’s suggestions, many of which Armstrong eventually got to when recorded Satchmo: A Musical Autobiography later that same year. But when Avakian sent it on May 11, Armstrong was doing multiple shows a day all over the United Kingdom. Glaser, made this clear in his reply of May 12 (the post office worked fast in those days), writing, “Since Louis is in Europe and I don’t know whether he has the various numbers you mention in his book or whether the men he has with him now are familiar with the numbers, I am not in a position to confirm any recording date in Chicago whereby Louis will play these numbers.” Here’s the full letter, which paints a good portrait of just how busy Armstrong was in May 1956:

Glaser wasn’t kidding. Armstrong arrived back in the States on May 28 and a bit of research on Newspapers.com shows ads for Armstrong appearances in Asbury Park, NJ on May 29, followed by Ocean City, Maryland on May 30, Baltimore on May 31 and finally, the Chicago concert on June 1. There would be zero time to prepare anything new (Armstrong’s old bassist Dale Jones rejoined the band in Asbury Park and had to learn any new repertoire, including recent recordings like “Mack the Knife” and “The Faithful Hussar,” right on the bandstand.)

The Chicago date was being regularly advertised in the Chicago Tribune by late May; here’s one such ad:

Finally, June 1 arrived. Here is a copy of the original concert program:

As can be seen on page three, an arbitrary list of tunes was included as being “probable” inclusions in the show, but that list was from Armstrong’s regular concert program and didn’t necessitate anything special. However, someone–maybe Avakian, most likely Glaser, DID finally get to Louis, quite possibly right before the show. In our Archives is a torn envelope with Armstrong’s name on it:

But on the flip side, in Louis’s handwriting and famed green ink, is the Chicago concert set list! Well, most of it; he never did get to “High Society” or “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans” as he began with the “Funeral March,” and he added a couple of things on the fly such as “On the Sunny Side of the Street” and “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue,” but this is pretty much how it went down, with the grouped segments following Hayes’s narration:

We will get to the music performed at the concert in a moment, but first, it should be noted that Helen Hayes’s narration has never been heard in public since June 1, 1956. Avakian didn’t release the recording of it at the time, Columbia didn’t release it when it first reissued the music on LP in 1980 or on CD in 1997 and Mosaic Records didn’t include it in its 2014 9-CD boxed set of live Armstrong recordings. One can assume that at this point, it most likely will never be heard. But for this anniversary, we thought we’d at least share Avakian’s copy of Jack Tracy’s script so listeners can get a sense of how the evening went down. Here it is, as recorded by Hayes before the concert, with Avakian writing in the song titles as they were to be performed at the actual concert (quick side note: both the script and Armstrong’s envelope refer to Louis opening up with two selections, “High Society” and “one more,” identified as “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans” in Armstrong’s note; but Sony’s 1997 reissue opened with the voice of Columbia’s engineer narrating that the concert is beginning with the funeral procession; thus, it doesn’t appear “High Society” or “Way Down Yonder” were performed and they definitely were not recorded but I suppose it is possible that they were performed before Columbia started recording):

After all that text, we need a photo to break matters up so here is the only one we have in our collection with Louis and Helen Hayes–not to mention Lucille Armstrong, Ed Sullivan and an unidentified couple on the right. I don’t think this was taken at the Chicago concert–Louis looks a little older and was on the thinner side in June 1956–but one never knows!

That concludes everything anyone possible would need to know about the events that led up to the Chicago concert–now onto the music! Fortunately, it’s easy to find so whether you have the aforementioned LPs or CDs or would like to stream along, now would be the time–here’s the Spotify link:

In 2014, I was co-producer of a Mosaic Records 9-CD boxed set, Columbia and RCA Victor Live Recordings of Louis Armstrong and the All Stars 1947-1958. For that set, we reissued the Chicago concert in full and I wrote about in the liner notes of the set. Here’s an excerpt of my notes; and because there’s somehow no surviving photos from the evening, here’s one of the same iteration of the All Stars–Louis, trombonist Trummy Young, clarinetist Edmond Hall, pianist Billy Kyle, bassist Dale Jones and drummer Barrett Deems–performing at the Sands in Las Vegas in the summer of 1956:

Though it had been an exhausting year, the band doesn’t sound remotely tired in Chicago. Lesberg didn’t stay on with the band when it returned to America, so Dale “Deacon” Jones was called in to fill the bass chair. Jones had already replaced Shaw once before in the summer of 1951, staying for over a year. Though his solos sometimes fell apart a bit rhythmically, Jones’s swinging lines and great use of showmanship made a fan of Armstrong. On one of his private tapes, Armstrong related that the addition of Jones over Shaw elevated the quality of the band a great deal in his opinion.

The Chicago event was more of a show than a standard concert; along with Hayes’s narration, sets were built onstage and the All Stars had to indulge in a little choreography. Thus, the opening funeral medley featured the band marching into the hall, Barrett Deems playing a snare drum on the back of the wagon. Hayes then talked about the riverboat days and Louis playing with Fate Marable. Armstrong made some concessions to the show here, playing ultra-short versions of MEMPHIS BLUES and FRANKIE AND JOHNNY before settling in on a lightning-paced version of TIGER RAG. Armstrong loved performing that number in Milan and after Ambassador Satch was released in late April, it made its way into the repertoire. He dominates this version more than in Milan—perhaps because he wasn’t as exhausted.

After Hayes discussed the closing of Storyville, the All Stars returned for wonderful versions of DO YOU KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO MISS NEW ORLEANS (taken at a perfect tempo) and BASIN STREET BLUES, which Armstrong had commandeered back from trombonists [Jack] Teagarden and Young after he successfully performed it in the film, The Glenn Miller Story. BLACK AND BLUE offers a nice change of pace at this point. A staple in the early days of the band, it disappeared in the early 50s until it showed up as a highlight of Avakian’s 1955 album, SATCH PLAYS FATS. Armstrong had performed it for Gold Coast Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah just a week earlier, Murrow’s cameras catching Nkrumah wiping a tear from his eyes. Armstrong’s opening is off-microphone but he still sings Andy Razaf’s heartbreaking lyrics with plenty of feeling.

WEST END BLUES opened up the Chicago section of the show, after Hayes discussed Armstrong’s records of the 1920s, “some of the most glorious discs ever produced” according to Tracy’s script (no argument here). Unfortunately, the famed cadenza and first chorus are both off-mike, but with that gigantic tone of his, you can still tell that he nailed it. Armstrong’s breath control was better in Chicago than in Milan, as he holds the climactic high Bb a bit longer, but his tone on the following runs was stronger in Milan. Still, it’s always a pleasure having another version of this demanding showpiece.

Our second visit with ON THE SUNNY SIDE OF THE STREET finds it taken at a medium tempo that is ideal for swinging, but still given the characteristic oomph that was a hallmark of this edition’s rhythm section. It’s a compact performance with Armstrong only singing one chorus, but it’s still a great one, the concluding trumpet work always raising the hair on my arms. STRUTTIN’ WITH SOME BARBECUE, concludes this portion of the program in its regular All Stars arrangement, perhaps a little quicker than usual, which only results in more fireworks from the front line.

At that point, Armstrong announced an intermission with a bit of WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH. In his notes to the 1997 reissue, Avakian wondered if Armstrong prematurely called this because he was sick of following the program. In actuality, Tracy’s script calls for an intermission at this exact moment, with Hayes opening the second half with a section about New York. This, however, seems to be the moment where Armstrong called off the shenanigans. Tracy’s script called for the All Stars to start playing MANHATTAN softly to commemorate Armstrong’s arrival in New York. She would then read two paragraphs summing up Armstrong’s career from 1929 to 1947 and then Armstrong would have the stage to himself.

However, the All Stars seem very hesitant on MANHATTAN probably never having played it before, as Armstrong plays the “A” section twice before jumping to the end. Then, instead of waiting for Hayes or any other cues, Armstrong’s plays a patented lick and segues right into a full WHEN IT’S SLEEPY TIME DOWN SOUTH. It’s not known if Hayes ever got to read her two paragraphs but it seems doubtful; Armstrong was now ready to do his show and though the script alluded to a set of “40 minutes or more,” Armstrong wouldn’t do less than an hour.

And what an hour it is. Armstrong was already well warmed up when he called his usual warm-up, INDIANA, so he is in extra fine form on this version. After five years of tinkering with it, Armstrong finally had a set solo he was proud of, the final piece being a quote from I COVER THE WATERFRONT he had recently added. This is the INDIANA solo and it’s a great one; critics carped but how could you improve on it?

Then we finally get to hear THE GYPSY after Armstrong quoted it on the two earlier 1947 concerts. He finally got to record it for Decca in 1953 and performed it almost every night from 1954 through 1956. Some might have written it off as a simple pop tune but it’s a tremendous showcase for all of Armstrong’s talents: his opening chorus is a textbook lesson in how to play a melody, then he sings the hell out of it ([Dan] Morgenstern has pointed out that you could hear what Billie Holiday got from Armstrong when listening to him sing this tune), he gets some laughs with his asides to the original lyrics (“Though I know she’s lying!”) and then picks up the horn for a half-chorus of improvising (never the same phrasing twice), with one of those endurance-taxing high note endings.

Next up, fresh from AMBASSADOR SATCH, comes THE FAITHFUL HUSSAR, still being introduced as “Huzzah Cuzzah” (“Something like that,” he could be heard saying when Trummy Young breaks up at his announcement). This must have been one of the first times the band performed it live because the tempo is faster than any ensuing version. Though it loses some of the “rocking” quality of the Milan version, there’s no denying that this version swings like mad. Armstrong clearly had a ball playing it, not wanting it to stop as he calls encore after encore. The tempo would drop a bit in the near future but Armstrong now had a new staple he’d perform until the late 1960s.

Up to this point, it has been all trumpet, something that Avakian probably didn’t appreciate fully in 1956, but something that has made this such an important document of Armstrong’s 1956 superpowers. Finally, on ROCKIN’ CHAIR, Armstrong takes a long rest from the horn to goof around with Young (though not a total break; playing that bit of melody at the start in the upper register is still quite demanding). I like Armstrong and Young’s camaraderie, though it’s different from the more loving bond between Armstrong and Teagarden. Armstrong and Young were two natural hams who loved telling jokes offstage, so they latch on to that aspect of their personalities to deliver an infectious performance of the old routine.

After that “break,” the All Stars really get the blood pumping on MY BUCKET’S GOT A HOLE IN IT. Though he had performed it with the All Stars for years, it really entered another realm when Hall joined the band. Armstrong realized this and almost every surviving version from the Hall era features multiple encores, each one more intense than the one that preceded it. A ridiculously exciting performance, only rivaled by a version from the Hollywood Bowl later that summer.

(In case you’re wondering about the encores, this was something that Armstrong learned in New Orleans, when the “second line” would demand brass bands play encores of well-received numbers. In the All Stars era, Armstrong fell back on this practice, not only because it generated a positive reaction but also because those 10 or 15 seconds of applause allowed Armstrong’s chops to regenerate and get ready to do it all over again, usually ending up pushing himself harder and higher with each encore.)

Finally, it’s time for the All Stars to take their features, Billy Kyle up first with his venerable PERDIDO before Hall sets off fireworks with a version of CLARINET MARMALADE even hotter than the attempt from Milan. MACK THE KNIFE follows and breaks it up as usual. Interestingly, Armstrong next calls his waltz-medley of TENDERLY and YOU’LL NEVER WALK ALONE, which was usually reserved for a change of pace, allowing Armstrong to play dramatic lead on two of his favorite standards. But starting in 1956, Armstrong almost always called it after MACK. I sometimes wonder if this was to quash any possible riotous reactions in these early days of rock and roll riots (a review of Armstrong’s recording in The Gramophone warned about MACK’S “unnecessarily long, and in places, revolting lyric that might easily incite impressionable teenagers to violence (and has had that effect in America, I understand).”) The waltz medley at least allowed everyone to relax a little bit.

But not for long! Deems is up next with his usual feature (and the feature for all All Stars drummers post-Sid Catlett), STOMPIN’ AT THE SAVOY. When Deems’s name elicits cheers from the crowd, Armstrong makes the connection that it’s because Deems is a “Chicago boy.” Armstrong loved Deems’s ability to work up a crowd; knowing he had many hometown friends in the house, Armstrong lets Deems go, offering more encores than usual, making this one the longest surviving versions of SAVOY.

Trummy’s next with his big feature from the Lunceford days, MARGIE. When he joined the All Stars, Young not only stepped up the tempo on it, but he also stepped up the showmanship, using his foot to play the trombone slide on the encores and eventually fake “collapsing” on his back at its conclusion. We can’t see any of that on this performance but we sure can hear Armstrong’s remarkable upper register playing on the encores. He performs that way all night, never taking a single song off.

“It’s blues time, folks,” brings Velma Middleton front and center with her showpiece, BIG MAMA’S BACK IN TOWN. For years, the climax was Middleton’s split but by this point, her obesity was beginning to slow her down. Not only does it sound like there’s no split on this version, but if you listen to the last chorus here, it ends after only four bars; it had been a full 12 bars during versions in 1955 but clearly, that was leaving her gasping for breath a little too much. She’s still catching her breath at the start of THAT’S MY DESIRE but that doesn’t stop her and Armstrong from doing their usual, side-splitting job of breaking up the audience. What comedic timing they possessed! The Crew Cuts’ KO KO MO seemed like an unlikely number to make it into the All Stars book but Armstrong adapted it as a duet between himself and Middleton. It had become a hit with audiences, something Armstrong and Middleton performed every night until Middleton tragically died while on tour in Sierra Leone, Africa in 1961. One fun aspect of the various surviving versions is the opening vamp on which Armstrong improvised a new solo every night, often sneaking in as many different quotes as he could fit. This one includes THE PEANUT VENDOR, WE’RE IN THE MONEY, YOU ARE TOO BEAUTIFUL and a witty comment on the surroundings, CHICAGO (THAT TODDLIN’ TOWN).

A super short Deems feature on MOP MOP concludes the All Stars’s explosive set. Hayes was then brought back to read a “finale” speech about jazz being an international language before Armstrong played a crowd-pleasing version of WHEN THE SAINTS GO MARCHING IN and a dramatic STAR-SPANGLED BANNER to punctuate the evening.

*****************

That concludes my 2014 liner notes but it does not conclude the saga of what has become known as “The Great Chicago Concert.” The evening was a success, winning positive reviews in the Chicago papers, while raising $65,000 for the National Multiple Sclerosis Society. Here’s an recap that was picked up by the Associated Negro Press and run in many black newspapers (which always found a way to heap extra praise on Joe Glaser):

After all the drama surrounding the planning of the show, George Avakian was unable to be in Chicago for the actual concert. He trusted his Chicago engineer Mason Coppinger, who recorded Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy, to man the microphones. Coppinger did his best but there were two microphones onstage and Armstrong occasionally played to the in-house P.A. microphone, leading to him sounding off-mike, as discussed above. Coppinger sent the tapes of the concert to Avakian on June 4 along with the following note:

Coppinger referenced sending along the contract, which was not part of Chris Albertson’s Columbia file–but somehow ended up in the Jack Bradley Collection! Bradley wasn’t on the scene in 1956 so someone working at Columbia, maybe his friend Frank Driggs, must have slipped it to him. As Coppinger wrote, Armstrong’s name was signed by Associated Booking’s Freddy Williamson so it’s not a legit signature but it’s still fascinating to see the contract for the evening:

With the paperwork out of the way, Avakian finally down to listen to the tapes. All of his original suspicions about the night had come true: the script was weak, Hayes’s narration wasn’t worth listening to and Armstrong didn’t play any of his suggestions—in addition to playing portions of a few numbers into the wrong microphone. Avakian did use “Black and Blue” and part of the New Orleans funeral medley of “Flee as a Bird” and “Oh Didn’t He Ramble” on the Satchmo the Great soundtrack LP and he’d pass off “Indiana” as being from Armstrong’s forthcoming At Newport album, but that was about it.

Meanwhile, things had taken a turn with Joe Glaser over publishing rights of all things. After several heated exchanges, Glaser made it clear that there would be no exclusive contracts with Columbia–or any other label. There was too much money to be made by selling Armstrong’s services to the highest bidder and when Norman Granz of the newly formed Verve Records came calling in the summer of 1956, Glaser wrote to Avakian to request a list of songs Columbia had recorded because Granz didn’t want to duplicate anything on his forthcoming session pairing Armstrong with Ella Fitzgerald. Avakian’s dreams of recording a string of albums with Armstrong over the next decade–he had already started planning a collaboration with Duke Ellington’s Orchestra, who had just exploded on Columbia thanks to the album of their 1956 appearance at Newport–were over.

There were still some loose ends to take care of, including to make sure Armstrong and his men were paid double scale for the Chicago concert. Glaser wrote to Avakian on August 8 to inquire:

Avakian didn’t respond personally but instead had a secretary write the next day to assure Glaser than a check had gone out that day. Here’s a copy of the “Breakdown of Payment”; Armstrong received double $82.50 for a total of $165, about $1,620 in 2021 dollars.

Avakian used what he could from the Chicago concert and put the tapes back on the shelves. One year later, he left the label entirely.

Flash forward to 1967 and Columbia was in the middle of issuing its thriving “Greatest Hits” series, spearheaded by producer Bob Johnston. In May 1967, the label released Louis Armstrong’s Greatest Hits with a selection of tracks picked by Frank Driggs.

Because the album would (unfortunately) be “Electronically Re-channeled for Stereo,” Driggs had to make due with performances from the 1950s and 1960s only. He dug out the Chicago concert tapes and issued “Basin Street Blues” and “Struttin’ With Some Barbecue” for the first time, but that was it. The tapes were put back on the shelf and that’s where they remained….

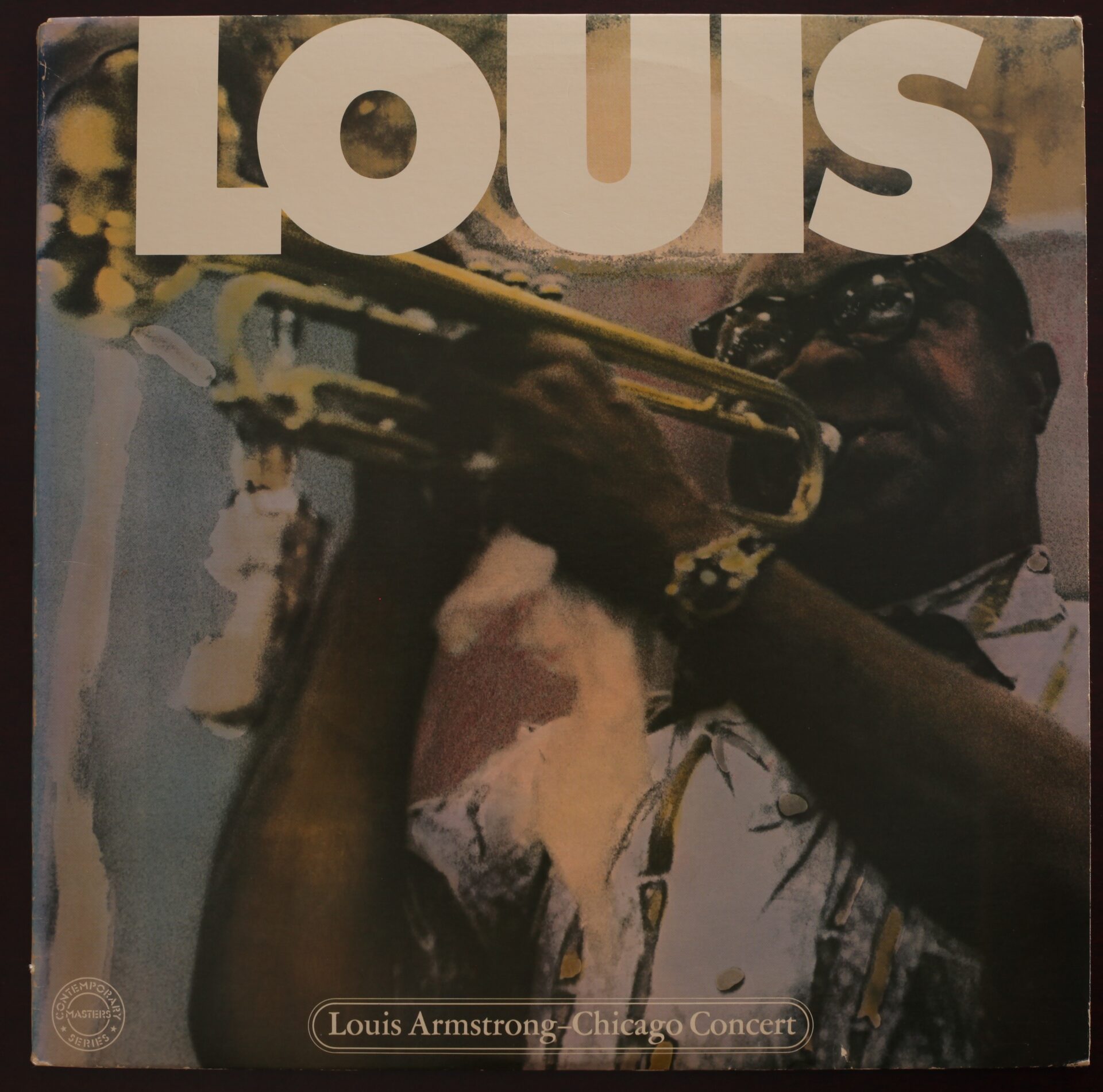

…until 1980. It was then that Columbia reissue producer Michael Brooks saw some reel-to-reel tapes about to be discarded from the vaults. He investigated and saw the full tapes of the June 1, 1956 Chicago concert. He rescued them and issued it as a two-LP set, Chicago Concert, eliminating Hayes’s narration and offering indispensable, Grammy-nominated liner notes by Dan Morgenstern. Armstrong had been dead for almost a decade and all worries about playing the same songs every night and Decca “five-year restrictions” had dissipated. Instead, the issue was fully embraced for presenting an incredible evening of entertainment from Armstrong’s most exciting edition of the All Stars.

In some ways, because of the contrived theme of the show, Chicago Concert actually showcased more full-on blowing by Armstrong than the usual All Stars evening as he was featured front and center on every number before the band got to let loose in the second half.

And though the band’s reputation for “playing the same songs every night” continues to dog them in some circles to this day, it’s worth noting what the band did NOT perform that night in Chicago: “A Kiss to Build a Dream On,” “Blueberry Hill,” “La Vie En Rose,” “C’est Si Bon,” “Ole Miss,” “Someday You’ll Be Sorry,” “Tin Roof Blues,” “Mahogany Hall Stomp,” “Ain’t Misbehavin’,” “Way Down Yonder in New Orleans,” “Royal Garden Blues,” “High Society,” “Twelfth Street Rag,” “Lazy River,” “Muskrat Ramble,” “St. Louis Blues,” “The Whiffenpoof Song” or “Back O’Town Blues.” For that list, I kept it only to songs that survive on other Armstrong live performances recorded between 1955-1957 (and I eliminated some songs they recorded for albums that weren’t regularly played–as far as we know–but should still count, things like “That’s a Plenty,” “When You’re Smiling,” “Jeepers Creepers,” “Old Man Mose,” etc.)

That concludes this long, long look at Louis Armstrong’s Chicago Concert. It might seem odd to spend so much time chronicling a concert that was just another one-nighter to Louis, something that wasn’t a defining moment like the W. C. Handy album and something that wasn’t even issued in his lifetime. But to fans of the All Stars–and the band actually seems to be gaining in popularity and respect in recent years–the night of June 1, 1956 represents a highpoint in a discography full of them. Plus, thanks to the foresight of people like George Avakian, Chris Albertson, and Michael Brooks, we thought it was worth bursting open our Archives to go behind the scenes and see how the business side of things worked back then, what it was like to negotiate with Joe Glaser, how it felt for George Avakian to be Louis Armstrong’s producer for such a fruitful two-year stretch, and so on.

But in the end all that matters is the music and as long as folks have access it, Louis Armstrong’s Chicago Concert will remain an unbeatable testament to a band at the peak of its powers.