“The Greatest Photo Taker”: Remembering Jack Bradley Part 47–Riverboat Benefit, Rainbow Grill with Duke Ellington, and USIA Film, 1969

We ended our previous post in a bit of a dark place: Louis Armstrong was in intensive care at Beth Israel Hospital for the second time in six months, Jack Bradley and Jeann “Roni” Failows called it quits after ten years of living together, Failows had a breakdown that landed her in the hospital, an ailing Armstrong snapped at Bradley for making a perceived dig at manager Joe Glaser, and Glaser had a stroke that resulted in his death on June 6, 1969.

Armstrong hadn’t performed in public since September (except for one brief appearance on Robert Morse’s TV show That’s Life–does anyone out there have a copy of it? Our Archives is missing both the video and audio–let us know!). Glaser’s stroke and eventual passing seemed to send Armstrong into a depression, though he did his best to combat it by throwing himself back into his reel-to-reel tape recording habit (we covered the tapes he made in this period in this series). It’s possible Bradley spent a little time with Armstrong at his Corona, Queens home in this period, but he didn’t take any photos or note any details if any such visits occurred.

And then on June 15, 1969, Armstrong suddenly reappeared in public–and Bradley was there with his camera! The occasion was a benefit for trumpeter Louis Metcalf, who apparently had fallen on hard times. Armstrong and Metcalf went way back, first meeting in St. Louis when Armstrong performed with Fate Marable on the riverboat in 1920 and sharing bandstands at the Lincoln Gardens in Chicago and at the Savoy in New York. The benefit was held at the Riverboat nightclub, located inside the Empire State Building, and featured a band with trumpeter Emmett Berry, trombonist and All Stars veteran Russell “Big Chief” Moore, clarinetist Herb Hall, and All Stars pianist Marty Napoleon. Though Bradley’s negatives no longer seem to have survived, we at least have the following four prints he made from the occasion:

Here’s Bradley’s recap of the occasion from the August 1969 issue of Coda:

“Louis Armstrong is still at home recuperating from his recent illness. He’s up to 137 lbs now and able to practice every day on his trumpet. Early in June he attended the annual Copacetics Ball at the Waldorf and went on stage and sang a chorus of Hello Dolly. On June 15 he attended the benefit for Louis Metcalf at the riverboat and got up on stage with Emmett Berry, Big Chief Russell Moore, Herb Hall, and Marty Napoleon and sang two numbers. He appeared in good spirits and was in fine voice. Needless to say he broke it up and received a standing ovation.”

Bradley was even interviewed by reporter Shirley Fischler, who wrote an article for the Toronto Star about Armstrong’s appearance at the Riverboat, even getting into questions of Armstrong’s finances in a post-Joe Glaser world:

The above article references Armstrong being “carefully guarded from the public,” noting that an official comeback would not be greenlit until Armstrong received approval from his doctors. That would not happen anytime soon, but the lure to perform again led Armstrong to once again hit the town on August 27, this time to sit in with Duke Ellington’s band at the Rainbow Grill at Rockefeller Center.

It was not Ellington’s full big band but instead an nonet with trumpeter Willie Cook, trombonist Lawrence Brown, reedmen Johnny Hodges, Harold Asbhy, Paul Gonsalves, and Harry Carney, bassist Paul Kondziela, drummer Rufus Jones, and Duke at the piano. Bradley was fortunately once again present with his camera–here’s one gem of Louis and Duke that he turned into a print:

Sadly, Bradley’s negatives from this didn’t survive either, but we at least have a contact sheet we were able to scan at a very high resolution, allowing us some precious glimpses at these two geniuses at work:

Bradley also got a few shots of those in the crowd, including Mercer Ellington and drummer Sonny Greer on the right side of the following photo; can anyone identify the others?

Once more, here’s a brief Bradley blurb from the December 1969 issue of Coda:

“In August, Louis went to the Rainbow Grill one night to present Duke Ellington with four Down Beat awards. He and Duke did some heavy mugging for the photographers, and Louis joined Duke and his band for a vocal rendition of Hello, Dolly.”

Armstrong then cooled it for much of September, going back to his tapes and scrapbooks, before embarking on a fairly busy (considering his health) October. First up was a short documentary film on Armstrong’s life that was being produced by Sidney J. Stiber for the United States Information Agency. Planning for the film went back to April 1969 and Jack Bradley was involved from the beginning; Bradley saved a two-page handwritten agreement he made with writer Ira Gitler, representing the USIA, noting that he lent Gitler 167 photos, 8 books, 1 award, 32 pieces of sheet music, and 15 records to be filmed by the USIA. In less than 10 years, Bradley had established himself as the world’s preeminent private collector of all things related to Armstrong.

Now it was time to film Armstrong’s interview, to be done at Stiber’s home in New Jersey in either late September or early October. Bradley found himself in a new role in his friendship with Louis, driving him and Lucille out to the destination; he would continue to serve as their driver to various events in the coming year (Jack used to joke that he wanted to wear a chauffer’s cap, but Louis wouldn’t let him). Once there, Bradley shot some images of Armstrong and Stiber with his usual black-and-white film. Yet again, there are no negatives, so these scans come from the contact sheet, opening with Armstrong and Stiber and Stiber’s camera:

I don’t know who the men on the ends are but in the middle, behind Louis, is longtime road manager Ira Mangel, back on the job:

Finally, Armstrong took his seat in front of the camera, as Stiber set up the scenery:

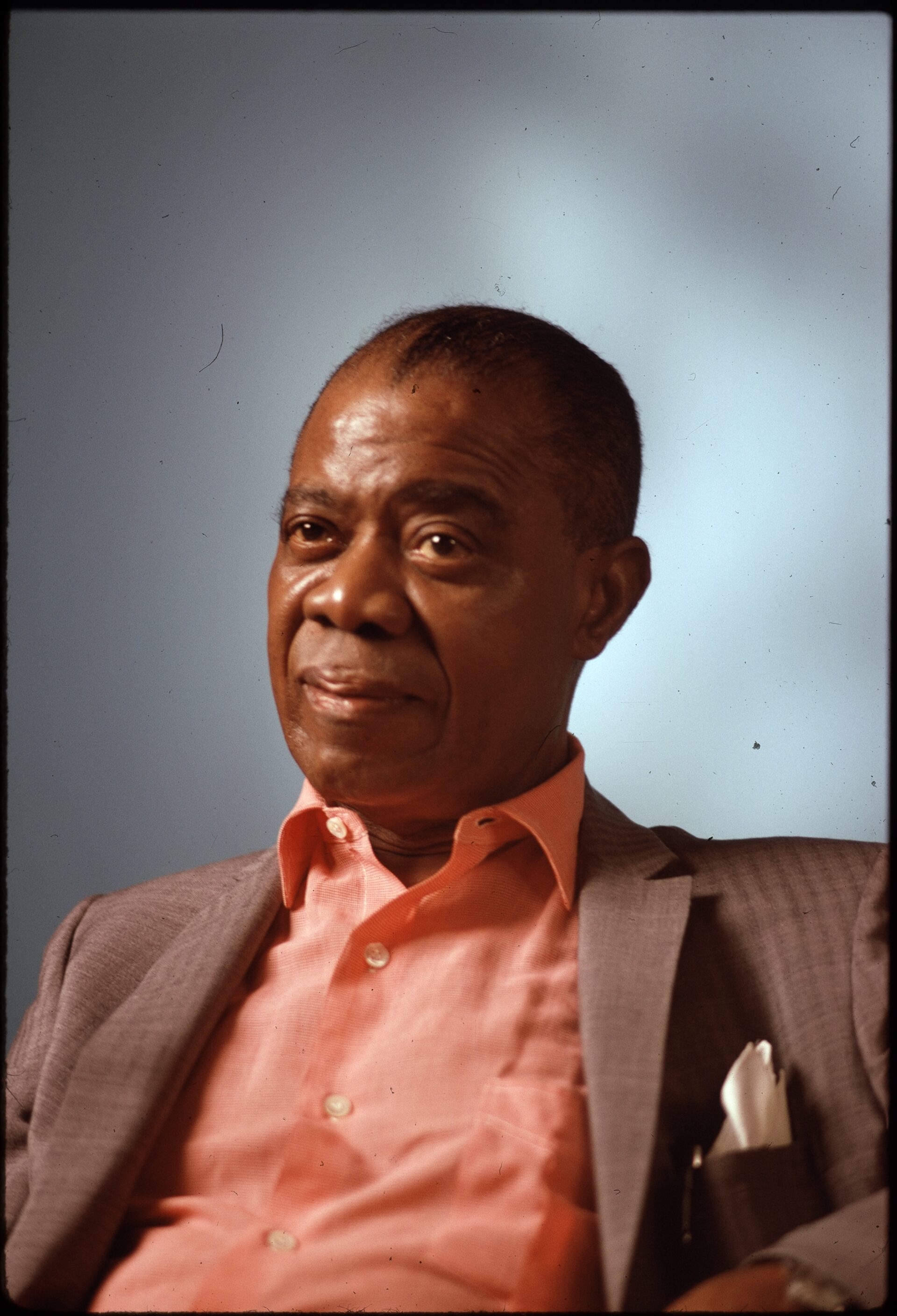

It was at this point that Bradley changed things up and did something we have rarely encountered in all 47 parts of this series–he switched to color film. The results are quite breathtaking:

The above shot only exists as a snapshot, but is still pretty striking. Not all of Bradley’s color photos came out as well, however; Bradley did struggle a bit with the lighting, though there’s still something appealing about this one:

This one is also way too dark but it’s our only evidence that Lucille was present:

But then Bradley, Armstrong, and Stiber stepped outside and Stiber’s garden provided an amazing backdrop for Armstrong to take part in an impromptu photo session:

Unfortunately, that’s the only shot we have a negative for but Bradley at least made snapshots of the series, which are still charming, even with the more muted colors:

Back to the negatives, Armstrong wanted to leave Stiber with a parting gift: a couple of signed copies of his latest LP release, ABC-Paramount’s What a Wonderful World, the album Louis finished in July 1968 to capitalize on the worldwide fame of the title track (fun fact: the cover of the LP featured a color photo Jack Bradley took of Louis at Freedomland in 1964):

Just to bring this particular story to its completion, here’s the finished USIA film, with footage from The Ed Sullivan Show, narration by Willis Conover, a ton of visuals from the Bradley Collection, and clips from Armstrong’s interview (shot in black-and-white). Bradley wrote about it in his October 1969 “Hot Notes” column and mentioned that he was told it would be seen by three billion people worldwide–let’s add a few more!

Soon after the shoot, Bradley ran into Louis and Lucille at Jimmy Ryan’s jazz club on 52nd Street on October 5. The Armstrongs had just come from seeing a production of Hello, Dolly, and according to Bradley, stayed at Ryan’s until the last note. While either hanging together at the film shoot or at Ryan’s, Bradley must have floated a dream idea past Armstrong: maybe Armstrong was too sick to go back on the road but wouldn’t it be great to take time, organize a dream band, pick the best songs, and make an album without any of the commercial tendencies that had taken over since the success of “Hello, Dolly!” On October 16, Bradley wrote a draft of a letter to Armstrong to put the idea in writing. Here’s the first two pages (and yes, Louis and Lucille did attend Game 5 of the 1969 World Series, watching the Miracle Mets take home the championship just a few minutes away from his Corona, Queens home–watch it on YouTube at 1:38:11!):

Bradley followed with several pages of possible song titles for this proposed 5-LP set. Alas, it’s not clear if Bradley ever edited the above letter and sent it off to Louis, but in the end, such an album was never made.

But one week later, Armstrong did find himself back in the recording studio for the first time in 1969 and Jack Bradley would be there–we’ll have that story next time.