“The Greatest Photo Taker”: Remembering Jack Bradley Part 5–60 Years of “The Real Ambassadors”

After Jack Bradley passed away on March 21, we launched into a multi-part series chronicling Jack’s famed friendship with Louis Armstrong. After publishing five parts (all of which can be read here)–and only covering the first 20 months of their relationship–we shifted focus over to the 50th anniversary of Louis’s passing.. That turned into a sprawling 17-part series (all of which can be read here) that took up just about the entire summer.

But we’re back to Jack today and the stars aligned because when we last left Louis and Jack, Louis was about to begin recording Dave and Iola Brubeck’s original work, The Real Ambassadors–60 years ago this week–making this the perfect time for an anniversary post dedicated to that landmark album, as well as a way to continue the saga of Louis and Jack.

The backstory of The Real Ambassadors is incredibly interesting and needs to be discussed before we get to the actual recording sessions. When Louis Armstrong spoke out against racial injustice in Little Rock in 1957, no one else in the jazz community supported him publicly, but privately, Dave and Iola Brubeck were moved by Armstrong’s courageous stance. The previous year, the State Department began sending jazz musicians around the world, leading off with Dizzy Gillespie. Armstrong was already beloved enough overseas to be nicknamed “Ambassador Satch” but after the events of Little Rock, he told the press that he wouldn’t go to Russia or anywhere else for the State Department. “The way they’re treating my people in the south, the government can go to hell,” Armstrong vented.

The following year, 1958, the State Department sent Dave Brubeck’s integrated quartet on a tour that spanned from behind the Iron Curtain into the Middle East and Asia. (For more on this tour, visit here.) Brubeck now had first-hand experience of how jazz was received overseas, but also saw how the State Department operated, urging the musicians not to speak out against racism or any other thorny issues back home, reminding them to be a “credit to their government.” (The Brubecks would satirize this on “Remember Who You Are.”)

Sufficiently inspired, Dave and his wife Iola set out to write a Broadway show that would show how jazz musicians made better ambassadors for the USA than real politicians. The work would get into issues of race and politics but would also feature a love story, costumes, singing, dancing and all the hallmarks of a big Broadway production.

The Brubecks wrote the entire script with Armstrong and Carmen McRae in mind. The first draft of what they called World, Take a Holiday was finished sometime in early 1959. The story cast Armstrong as “Pops Anderson,” a trumpeter who ends up in the fictional African country of Talgalla. He is mistaken for being a real Ambassador and is named “King for a Day,” triumphantly carried along the streets of Africa. Here are a few pages from Louis’s copy of the script, including the build-up to Armstrong’s emotional showpiece “They Say I Look Like God”:

While still finishing the script, Dave Brubeck and Armstrong found themselves in Chicago at the same time on December 27, 1958. Dave talked his way into Armstrong’s dressing room, told him about the project, and asked him recite the words one of his and Iola’s pieces, “Lonesome.” Armstrong’s passionate reading moved Brubeck tremendously.

On January 2, 1959, Dave and Iola saw Armstrong’s appearance on the TV show You Asked For It during which he gave a little monologue about being a jazz ambassador. Here is a copy from Louis’s own reel-to-reel tape collection:

Since the sound quality isn’t very clear, here’s a transcription:

“Hi everybody. Say, Jack, I think you’re wrong about ME being the ambassador. I think JAZZ is the ambassador. One might be the courier that takes the message over there, but it’s jazz that does the talking. That’s the good thing about our kind of music: it speaks in every language and it’s understood by everyone that wants to listen. My horn and me have traveled from Sweden to Spain and when I played Berlin, a lot of them cats jumped down first to hear ol’ Satchmo! Which proves that music is stronger than the nation. I don’t know much about politics, but I know these people in foreign countries hear all kinds of things about America, some good, some bad. I’m pretty sure what comes out of this horn makes them feel better about us. One thing’s sure: they know a trumpet ain’t no canon! This horn is my real boss. It’s my living and my life. I’ve got a lot of high notes in me that haven’t been blown yet. Yeeaaah.”

Many of the themes present in World, Take a Holiday appear in this clip. The Brubecks were inspired to take out a reel-to-reel tape recorder to record themselves telling Louis more about the project. Towards the end, Dave even sat at the piano to play–and sing!–snatches of “Lonesome” and “Summer Song.” Here is Dave and Iola’s tape, copied from Louis’s collection (with aural watermarks to prevent commercial use without further permission):

LAHM 1987.3.191

As referenced in the tape, Dave knew that Louis would soon embark on a tour of Europe and it would be difficult for him to devote much attention to the production. Indeed, Louis would be in Europe for six months and after a short period convalescing from a heart attack suffered in Spoleto, Italy, spent the rest of 1959 and the first half of 1960 performing a seemingly endless string of one-nighters. Brubeck meanwhile scored a hit in 1959 with the release of the LP Time Out and was touring constantly himself (also booked by Armstrong’s longtime manager, Joe Glaser). World, Take a Holiday would have to be put on hold.

In October 1960, an incredible thing happened: art imitated fiction when the State Department sent Louis to Africa, just as described in World, Take a Holiday! When Armstrong’s presence stopped a civil war in the Congo, photos hit the wire services of Armstrong being carried in Africa, just as the Brubecks had written it in their production. An editorial that appeared in many newspapers in November 1960 basically underscored the entire point the Brubecks were trying to make: “Having been around the world numerous times, and as a representative of the State Department, this man with his trumpet is able to overcome barriers between peoples in a way beyond the capacity of polished diplomats.”

Armstrong returned from his overseas tour in February 1961. Brubeck, already riding high from the success of the album Time Out, received another boost when a single of “Take Five” was released in May 1961 and reached number 25 on the Billboard Hot 100. Brubeck decided to strike while the iron was hot and, knowing that it wasn’t yet possible to get the full-scale version of the show on Broadway, insisted Columbia sign Armstrong, Carmen McRae and Lambert, Hendricks and Ross to record the score of what was now being called The Real Ambassadors in September 1961. It wasn’t cheap; at Columbia, some executives referred to it internally as “the most expensive demo ever made.”

Studio time was booked for two dates on September 12, two more on September 13, one on September 19, another on September 20 and finally, some of McRae’s solo features would be waxed on December 19. Teo Macero would serve as producer and would be in the booth for all sessions.

All that remained was to get the 60-year-old Armstrong up-to-speed to learn 15 challenging Dave Brubeck compositions ahead of time. Brubeck did his best to prepare Armstrong before the sessions, sending him all the music in advance, including the lyrics on index cards, which are now part of Jack Bradley’s collection. Here’s one for “I Hear a Trumpet” which became part of the “Swing Bells” finale on the LP:

The handwritten “YEA-YEA” on “Everybody’s Comin’” in Louis’s handwriting:

In the script for World, Take a Holiday, the other main male part is “Saul,” but by September 1961, Brubeck knew this would be perfect for Louis’s regular trombonist, Trummy Young:

All of the index cards were sent to Joe Glaser in a letter postmarked August 16, 1961, as evidenced by the envelope Bradley kept:

Brubeck made more tapes where he demonstrated the songs and offered verbal instructions for Louis could do with them. Here’s his explanation for “Blow Satchmo:”

Brubeck even booked rehearsal time for Armstrong and his All Stars. Armstrong brought his tape recorder to one of the rehearsals, so he could study the routines in his downtime, training like a boxer before a title fight. Here, from September 18, the day before the official session, is “Remember Who You Are,” at a slower tempo than on the record and with Armstrong and Young working on a little comedic dig at Russia that didn’t survive the evening. For the 60th anniversary, here is the entire 18-minute tape, watermarked again:

Sufficiently prepared, Armstrong entered the studio September 12 to begin recording his parts for The Real Ambassadors. For a thorough portrait of what happened in the studio, allow me to recommend Mosaic Records’s new 7-CD boxed set The Complete Louis Armstrong Columbia and RCA Studio Sessions 1946-1966 with the full disclosure that I served as a co-producer of the set and wrote the liner notes booklet, which includes over 6,500 words on The Real Ambassadors alone. The set includes the original album, as issued in 1962, plus an entire 75-minute disc of previously unissued bonus materials and alternate takes. If that sounds like overkill, the original album is easily found on all streaming services and you can probably still find the 1994 Columbia CD at a good price.

But to bring Jack Bradley back into the story, Jack was there for Louis’s sessions and took copious photos–and copious notes. I’ve quoted from these notes in my book and liner notes, but here they are in full, published for the first time:

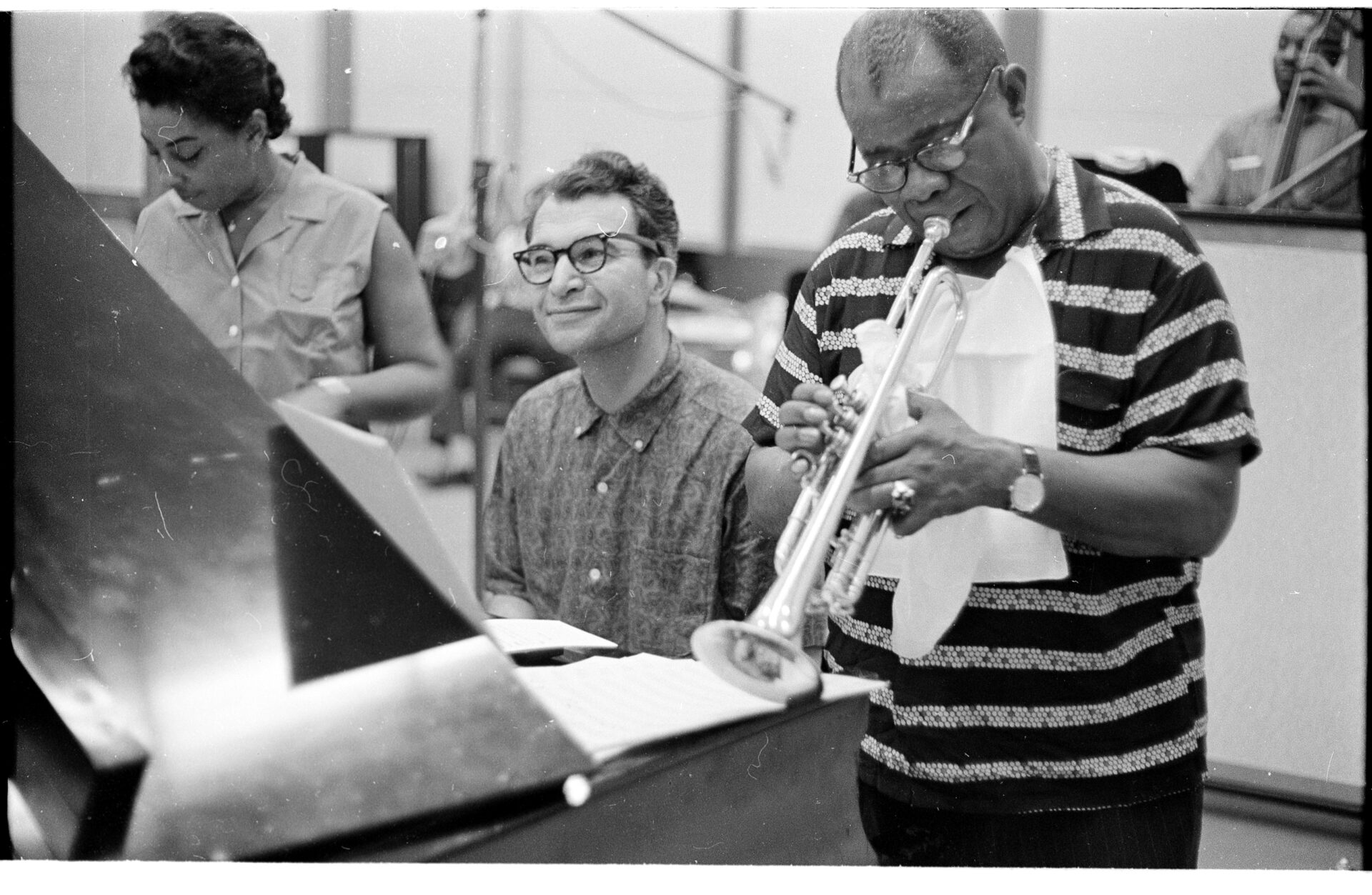

Naturally, Bradley brought his camera to the sessions and snapped over 50 photos from the dates–here are some of our favorites!

Anyone notice a common theme to the above photos? In the 53 photos Jack Bradley snapped, Louis Armstrong is not broadly smiling in a single frame. This is not to say he wasn’t happy; on the contrary, he was extremely proud of this work, telling folks “Brubeck wrote me an opera!” But he was deadly serious during the recording dates to reflect the serious nature of much of the music he was asked to interpret; he knew this was a challenge and was focused on owning this material. Anyone who listens to the final album will know that he passed with flying colors.

Jack Bradley wasn’t the only photographer there. Burt Goldblatt also shot several dozen photos, which we have at the Louis Armstrong House Museum, but we do not have the rights so will not share them here–except two: the only photos from the week that give us a glimpse of Jack Bradley!

The Real Ambassadors was issued by Columbia in 1962 as a gatefold LP with liner notes by Gilbert Millstein and Iola Brubeck. Here’s Louis’s copy, the back cover making good use of a photo of Louis in the Congo in 1961:

That same year, in September 1962, The Real Ambassadors had its first–and only–performance at the Monterey Jazz Festival. It was a scaled down one-hour version and the cast read their parts from scripts on music stands but it ended with a standing ovation and was the talk of that year’s festival. Unfortunately, Joe Glaser didn’t allow it to be filmed and no one–not even an amateur in the audience–recorded it so nothing survives from the Monterey performance except some photos.

After the performance, Dave and Iola Brubeck sent a congratulatory telegram to Louis Armstrong–an artifact saved by Jack Bradley and is still a part of his collection today:

Because of the somewhat controversial subject matter of the piece–and because, without the script, the album seemed a bit disjoined–The Real Ambassadors became the lowest-selling Brubeck LP in his long association with Columbia. There were no further broadcasts of it and it disappeared from public consciousness fairly quickly. Yet both Armstrong and Brubeck remained proud of it, the trumpeter dubbing his copy to tape numerous times in his final years, while Brubeck seemed to mention it in almost every interview he gave before his passing in 2012.

In 2020, the Louis Armstrong House Museum teamed up with the Forum for Cultural Engagement through the U. S. Embassy of Moscow to shoot a special filmed version of The Real Ambassadors in the historic homes of both Armstrong and Brubeck. The film features Jake Goldbas, Artistic Director/Drums; Alphonso Horn, Trumpet/Vocals; Camille Thurman, Saxophone/Vocals; Vuyo Sotashe, Vocals; Marie Johns, Vocals; Chris Pattishall, Piano; Endea Owens, Bass. You can watch the entire 55-minute concert HERE and the trailer below:

That concludes our look at the 60th anniversary of The Real Ambassadors but definitely check out the recordings to hear a work that was years ahead of its time and still has to the power to surprise us and make think all these years later. But this does not conclude our tour through the friendship of Louis Armstrong and Jack Bradley as we’ll be back with more posts and much more content in the very near future.