“They’re My Tops”: The Making of “Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy”

Louis Armstrong made dozens of albums in the long-playing era but for many–including Louis himself–one stands out above all others: 1954’s Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy, recorded for Columbia Records and produced by George Avakian.

Earlier this month, Mosaic Records released a limited edition, 7-CD boxed set, The Complete Louis Armstrong Columbia and RCA Victor Studio Recordings, 1946-1966. (Full disclosure: the author of this piece is one of the co-producers of this set and also wrote the liner notes for it.)

The centerpiece of the set is a straight reissue of Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy in remastered sound, plus over 100 minutes of bonus materials, including alternate takes, rehearsals, discussions, insert takes and more. It’s a definitive portrait of Armstrong and the All Stars in the studio, working with Avakian to create a true masterpiece.

But how did Louis Armstrong prepare for the sessions? That’s the theme of this unique “That’s My Home” post, which will give a unique perspective on Armstrong’s creative process.

It’s sometimes assumed that Armstrong spent his days and nights on the road with the All Stars and then turned up for the occasional recording session, usually seeing the material for the first time when the date began. That definitely did happen on occasion–such as Armstrong’s Verve recordings with Ella Fitzgerald and Oscar Peterson, where the tunes were decided on the spot, keys were worked out, and they were off and running.

But oftentimes, Armstrong knew exactly what he was going to do when he entered the studio. In 1949, Armstrong ended up back at Decca, recording his own unique interpretations of other people’s hits under the guidance of producer Milt Gabler. Gabler had an incredible knack for knowing just what numbers on “Your Hit Parade” would suit Armstrong to a tee. The results were some of the most popular recordings of Armstrong’s career: “Blueberry Hill,” “That Lucky Old Sun,” “La Vie En Rose,” etc.

At our Archives, we have Armstrong’s famed private reel-to-reel tapes. On those tapes exist recordings of Armstrong singing a capella versions of some songs he was to record for Decca, including “I Laughed at Love,” “Congratulations to Someone,” “The Whiffenpoof Song” and others. Oftentimes, Gabler also sent him the hit version, too, so Louis would dub say, Sunny Gale’s “I Laughed at Love” and then record himself singing it by himself. One can assume that he’d spend several days listening over and over so when he hit the studio, he was ready.

That’s the backdrop for today’s post, which will focus on Armstrong similarly preparing for the W. C. Handy date. George Avakian had been an Armstrong friend since he first discovered a series of unissued Armstrong recordings from the 1920s in Columbia’s Bridgeport vault and issued them on the pioneering Hot Jazz Classics series in 1940. Avakian grew closer and closer to Armstrong over the years, spending several hours with him at his home in Queens in 1953, all of which are captured on tape. Friendship was one thing, though; producing an album was another and Avakian salivated to get the opportunity to record Armstrong in the studio.

Avakian got wind that Armstrong’s five-year contract with Decca was due to expire in the spring of 1954, after an April date for that label. Avakain sprung into action and met Armstrong’s manager Joe Glaser for lunch with an offer he couldn’t refuse. Armstrong received flat payments and no royalties for his landmark Hot Five and Hot Seven recordings of the 1920s; Avakian promised that royalty checks would start coming in if Glaser allowed Avakian the opportunity to record one album with Glaser’s star client. The deal was made.

Avakian wanted Armstrong to initiate a series devoted to great composers in jazz and dreamed that Armstrong would eventually record the music of Fats Waller, Duke Ellington, King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton and others (only one of those would get made by Avakian). But first, the inaugural release would be devoted to “The Father of the Blues,” W. C. Handy.

Avakian went to a music store and bought commercial sheet music of 12 Handy compositions. For each one, Avakian typed up some notes on how he thought Armstrong’s performance should go, and stapled them to the cover. All 12 copies were sent to Armstrong, who wrote the word “KYLE” on the cover of each one. That was a reference to his pianist Billy Kyle, a fairly recent hire who would stay for 13 years and always acted as Armstrong’s de facto music director.

But before sending them over to Kyle, Armstrong turned on his tape recorder while at home one day with his wife Lucille and decided to run them all down on his trumpet and with his voice. That’s the good news.

The bad news? At some point in the late 1950s, Armstrong’s tape collection, according to his count, was pushing a thousand and he was having trouble cataloging it all and keeping it straight. He bought a new machine in 1958 and decided to consolidate some of his older tapes. How did he do it? He would take a tape he recorded earlier, most likely at 7 1/2 or 3 3/4 ips speed and start playing it one one reel-to-reel tape player. He then got his new tape deck, spun a blank tape and just held a microphone out to catch the sound from the original tape through tinny speakers. Sometimes the microphone would be on the far side of the room and he’d capture himself in conversation with others. And when he was done, he simply erased the original tapes and continued onward, taking those tapes, which originally were about an hour long, and jamming them together until he had 3, sometimes 4 hour tapes….that were one step away from being unlistenable.

And unfortunately, Armstrong’s preparation for the Handy album is one that got that treatment. After going through all 700+ tapes in our Archives, the material we’re about to share in a moment only survives on this one tape in this putrid sound quality, but hopefully you can put on some headphones and Armstrong’s magic will still shine through. (Though as on other such posts we’ve shared with long excerpts from Louis’s tapes, we’ve included an aural watermark, an occasional “beep” to prevent any commercialization on the audio contained herein.

Also, recordings have survived of only five of the Handy compositions; it’s not known if he did the rest, but we’re thankful to have these, nearly half the numbers on the finished album. On the positive side, the sheet music for all 12 numbers does survive in our Archives and we’re going to be sharing pages from those, too, especially as they contain some further intel on different aspects of studio recordings.

Armstrong opened the proceedings with an introduction–even though there was no audience present but Lucille–before launching into “Aunt Hagar’s Blues.” Here’s the audio of this moment:

As a means of translation, here is what Armstrong says at the start of the track:

“Getting ready to record 12 Handy numbers, maybe more. [Lucille speaks inaudibly in the background, telling Armstrong to specify who he’s talking about] W. C. Handy, that is. That’s [unintelligible] Louis Armstrong, and Lucille Armstrong, speaking. W. C. Handy, she’s right. Let the woman tell you all about it, eh, boy?”

Armstrong then reads Avakian’s note, which no longer survives: “First number, ‘Aunt Hagar’s Blues.’ Introduction, verse and chorus should be sung once through and the rest instrumental.”

And here’s the sheet music Armstrong was reading from, with an unfortunate racist cartoon on the cover; it’s startling that this was still available in 1954:

For anyone who would like to read along while listening to Armstrong’s rehearsal or to the recording, here’s what he was using:

Armstrong then turned to Handy’s most famous composition, “St. Louis Blues,” a song Armstrong had been performing for decades, recording seminal versions with Bessie Smith in 1925 and with his own big band for OKeh in 1929, for RCA in 1933 and for French Brunswick in 1934. Live broadcast versions survive from the 1930s big band era and also from the early All Stars period before Earl Hines joined the band and commandeered it as his “Boogie Woogie on the St. Louis Blues” feature.

On this recording, Armstrong plays the melody down off the sheet music but then really relaxes and improvises beautifully for a few minutes:

At the very end, Louis says, “Lyrics we don’t have to record, we know them.” But in the studio, Armstrong and Velma Middleton decided to stretch out and tossing the sheet music aside, ad-libbed some of their favorite stanzas, Middleton singing about “taking her time” and Armstrong responding with a politically incorrect chorus he originally sang on a Martin Block jam session with Fats Waller and Jack Teagarden in 1938, threatening to grab a picket off a fence “and whip your big head ’til you learn some sense.”

On the Mosaic set, we have included the first complete take, take 3, and three minutes of discussion that immediately followed that Avakian captured by just letting the tape roll. During the discussion, Armstrong and Middleton express discomfort that their ad-libbed lines might not pass the censors. They reach for the sheet music and start going through the printed lines, Armstrong trying the “blonde-headed woman” one on for size before Velma shoots it down. He then gets to the last line in the sheet music, “If my blues don’t get you, my jazzing must.” Armstrong quickly offers a substitution of the tamer “my jazz music must” but Avakian disagrees, pressing him to sing “jazzing.” “Well, what the hell, we’ll leave it as it is,” Armstrong responds on the next take, they did just that.

But analyzing Armstrong’s copy of the sheet music also offers insight into he phrased his first vocal choruses about going to see a gypsy, as those lines are in the sheet music but about the reek of out-of-date dialect. Armstrong retains the flavor but inserts his own personality into them, improving Handy’s written text and making it his own.

Here’s Armstrong’s copy, with the first instance of “KYLE” in parentheses on the cover, written in Armstrong’s hand:

Armstrong was also no familiar with the next song Avakian sent him, “Ole Miss Blues.” It was the first song Kid Ory remembered the teenaged Armstrong playing with his band in his apprenticeship days in New Orleans, plus it was in the All Stars’ book as the part of the regular drum feature on “Bugle Blues” (also a Handy composition). Armstrong announces, “The next one is ‘Ole Miss.’ It says here on this piece of paper…” and then reads Avakian’s notes. Unfortunately, he becomes inaudible but this is the one of only two scores where the original note has survived, which we’ll share below.

First, though, Louis unaccompanied for nearly two minutes, reading the verse and main strain off the sheet before wailing in the last chorus:

And the sheet music, with Avakian’s note:

Next is really the main event in terms of something that’s almost completely different from what’s on the album: “Hesitating Blues.” Armstrong opens by saying, “Next one, ‘Hesitating Blues.’ And the rundown [by Avakian] says here, ‘Despite the reputation this number has, it is not too great vocally. Maybe it should be done as an instrumental. Louis and Velma should kick the vocal around and see how they feel about it. Well, we’ll see.”

And with that, Armstrong picks up his trumpet and plays the entire thing down. He’s super comfortable with the familiar verse and phrases it in his own fashion almost immediately but then he gets to the chorus and plays it closer to what’s written. He then returns to the start and barks out, “Vamp!” before playing the verse one more time. At that point, he sings the whole thing from start to finish; his “good number for tomorrow” improvised response is in place as it would be on the record.

For those who know the album, Avakian, most likely with input from Armstrong and Kyle, decided to scrap the chorus entirely and just have Louis, Velma and the All Stars stick to the verse. The result was a masterpiece but on this recording, despite the poor sound, we can actually hear Armstrong singing and playing on the “lost” chorus. Sit back and relax for 7 minutes and 26 seconds and enjoy Louis Armstrong rehearsing “Hesitating Blues”!

And here’s the sheet music he was using:

If you listened carefully to the end of “Hesitating Blues,” you’ll hear a drink being poured, followed by the quiet voices of Armstrong and an unidentified male talking–while Armstrong is speaking. What’s going on here? As discussed above, sometime in the late 1950s, while Armstrong was dubbing his original tape to a new compilation (and ruining the sound quality in the process), someone must have popped in, so Armstrong caught the conversation and the low level recording simultaneously!

Unfortunately, this continued throughout the fifth and final rehearsal recording, “Beale Street Blues.” It’s almost impossible to make out in the crosstalk, but Armstrong reads Avakian’s note (this is the best I can do to translate): “Vocal number, but omit the verse. Third chorus should be sung first and the first chorus should be sung later. Omit the second chorus . This number also lends itself to a long instrumental interlude.”

However, for once, Armstrong must have realized that his impromptu conversation obscured the tape he was dubbing so elsewhere on this same tape, he re-recorded “Beale Street Blues” and this time actually made sure to move his microphone a little closer to the other deck! Thus, this is still a long-way from high fidelity but it’s the best sound we have of this priceless moment (it was also featured in the early days of tours at the Louis Armstrong House Museum and a few television segments on Louis’s tapes from the early 2000s):

That’s a short one and Armstrong eschewed the lyrics most likely because he knew them, even though he had never previously recorded it. Here’s the sheet music he was playing from:

The sheet music opens with a long verse that takes up two pages; Armstrong followed Avakian’s suggestion and didn’t play or sing it, at home or in the studio. Interestingly, he did not follow the suggestion to sing the third chorus (“If Beale Street could talk”) first and instead sang the opening “You’ll see pretty Browns” stanza, before omitting the second chorus and going straight to “If Beale Street could talk”:

Sadly, that’s the end of the recordings but it’s not the end of the sheet music. We’re not going to share every page of every surviving sheet, but there are a few more examples that illuminate the final album.

For example, take the album’s final track, “Atlanta Blues”:

The performance–and the album–ends with a winking “Good evening, friends” line from the band. In his liner notes, Avakian wrote that the line “fractured” Armstrong when he first encountered it. Sure enough, on the Mosaic set, you can hear the fir the first complete take devolve into laughter when Armstrong and the band get to it. Here is the final page of the sheet music they were looking at, which does indeed go back to the verse–called the “PATTER” here–but the final phrase, as written, ends on the tonic, F. I think Armstrong expected it to go to the dominant 7th Eb and when it didn’t, he kind of froze of broke into laughter. They lean on the dominant 7th on the album, for that “Good evening, friends” finish.

On “Memphis Blues,” Avakian handwrote some changes to the lyrics. Here’s the cover:

Here’s the page with Avakian’s handwritten changes, which Louis followed on the record:

On “Loveless Love,” we have maybe the only instances of some chord change substitutions being written into the sheet music in the verse. Here’s the cover:

And here’s the verse with some handwritten changes (the rehearsal sequence where the pick the key and go over everything is included on the new Mosaic set):

“Chantez-Les Bas” is the only other song where Avakian’s original typed note has survived:

Even with Armstrong’s landmark recording, this tune has not exactly gone on to “standard” status. If any musicians out there would like to see what Armstrong had to work with, here’s the rest:

Another song worth examining in full is arguably the most infection track on Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy, “Long Gone (From Bowlin’ Green)”:

This is one where, listening to the session tapes, it appears Louis did not have time to even glance at before the session (it’s quite possible the five audio selections we shared earlier are all he had time to tackle before the session). Billy Kyle can be heard playing down the melody, picking a key, and giving trombonist Trummy Young and clarinetist Barney Bigard harmony notes to play. Within minutes, a routine is hatched, involving a chorus made up of the various friends and guests occupying the studio, a sequence that is also on the Mosaic set. For those listening along as Louis and Velma Middleton perform the number, here’s what they were looking at:

The last page contains a short note in Billy Kyle’s handwriting, “Band Cho Vamp,” shorthand for the routine.

“Yellow Dog Blues” doesn’t have any substantial changes between the score and the recording, but it’s worth sharing the cover, featuring a photo of Armstrong’s friend–and Columbia labelmate–Eddie Condon:

That makes the 11 songs heard on the album…but on the tape, Louis clearly said he had 12 songs in his possession. What was the 12th number? “Joe Turner Blues.” Armstrong ended up getting one of his Scotch tape collages stuck to it so it only survives in our Archives as follows:

That takes care of Armstrong’s preparation for the sessions, which took place in Chicago on July 12, 13, and 14, 1954. On the opening session, Armstrong and the band caught fire and recorded an incredible six selections in one night, taking care of “Aunt Hagar’s Blues,” “Hesitating Blues,” “Ole Miss Blues,” “Beale Street Blues,” “Loveless Love” and “Long Gone.”

The next night, they did three more, “Memphis Blues,” “St. Louis Blues” and “Atlanta Blues.” This time, Avakian hired photographer Fran Byrne to shoot the session, images that ended up in Jack Bradley’s Collection and are now part of the Mosaic Records booklet. We’ll share a few here because they directly involve the exact copies of the sheet music shared above!

Here’s Louis recording “Memphis Blues”:

And here’s Armstrong and Avakian going over the sheet music probably to decide what to record next:

In this image, Armstrong is running down some of the melodies as Avakian looks on; “St. Louis Blues” is on the pile, with Avakian’s note removed. Note that “Joe Turner Blues” is still in the pile up for consideration.

One more, this time with Billy Kyle joining in to look the music over (“St. Louis Blues” is now on the music stand, but Avakian’s note is still affixed, meaning this must have been taken before the previous photo and just before Louis recorded that epic 8 minute and 50 second version of “St. Louis” that opens the album).

And just to give listeners an idea of the set up of the studio (located in the Wrigley Building in Chicago, most likely WBBM radio’s studio), here’s the vocal microphone in relation to the rest of the band:

And here’s where Louis would blow. Trummy Young and Barney Bigard are visible, drummer Barrett Deems and bassist Arvell Shaw are obscured.

The sessions ended on July 14 with the recording of “Chantez-Les Bas” and “Yellow Dog Blues.” Avakian then went to work, editing and splicing together his finished masters. The Mosaic set contains all of Avakian’s final edits, but it also includes alternate takes of every single song recorded for the album to give a taste of what it sounded like in the studio before the edits were made.

Avakian took copious notes on each take of each selection before making his edits. Sometime in the late 1970s, Chris Albertson was working at Columbia Records and noticed Armstrong’s file was about to be thrown away. He saved it and in 2016, donated it to the Louis Armstrong House Museum. This might be getting far afield from the “That’s My Home” theme but here are some of Avakian’s pages in which he takes notes on each take, something that was crucial to follow when putting together the Mosaic set. The first two pages document the productive July 12 session:

Here are pages related to the July 13 date, including Avakian’s blow-by-blow on two complete takes of “St. Louis Blues” (both of which are included in the Mosaic set); it also includes Avakian’s calculations on how much to pay the band:

And finally, Avakian’s notes on the July 14 session, which ended with a Trummy Young showcase on “Tain’t What You Do,” heard on the Mosaic set but not a part of the Handy album:

With the edits done, Avakian, now had to sequence the album. This sheet includes an early attempt at the bottom, mostly crossed out, and the finished sequence up top, but still with some edits and changes up to the last minute:

Avakian worked tirelessly, but quickly and had the masters entirely edited by the end of August. On September 3, he invited Louis and Lucille Armstrong, along with W. C. Handy and his recently married wife, Irma Louise Logan, up to Columbia’s New York studios to listen to the finished–well, not entirely finished, but more on that in a bit–masters.

Handy, 80-years-old and blind, brought a gift: a copy of his book, A Treasury of the Blues. Photographer Guy Gillette was on hand to capture the moment Handy signed it for Louis as Avakian looked on:

That might be Avakian’s copy (Louis is holding another in the photo above). Here is Handy signing it for Louis and Lucille:

The Armstrongs brought Handy’s book home and that’s where it remained until the end of their lives; it is now a cherished piece of our Archives. Here’s the front cover:

And here is Handy’s touching inscription, “To Louis Satchmo Armstrong, William C. Handy, 9-3-1954.”

Armstrong and Handy listened to the album together, Handy often breaking into applause as tears came to his eyes. When it was over, Gillette snapped a photo of Armstrong–still holding the book–Handy, holding the reel of tape, and Avakian:

Avakian wasn’t completely finished, though. While he had Armstrong in the studio, he asked him to overdub trumpet and vocal obbligatos on “Atanta Blues.” Armstrong obliged as Gillette snapped more photos, many of which are in the Mosaic booklet. Here’s one, with All Stars drummer Barrett Deems, there to also listen to the master takes, in the background:

That same day, Gillette also took numerous photos of Armstrong and Handy seated together, one of which became the album’s iconic cover photo. Here’s an alternate take with Avakian there, too:

With that, Armstrong had to leave the studio and prepare for his evening gig at the Manhattan nightclub Basin Street. But first, he sat down for a conversation with Leonard Feather, profiling Armstrong for Esquire. “I’m tired today,” said Louis. “Been down to Columbia Records. They had some nice open spots on the tapes where I could fill in behind my vocals—dub in some horn accompaniment.” He hummed a few phrases and chuckled. “Man, a cat came in from Columbia and said we gotta make some more of these. It was an album of W.C. Handy’s blues. Mr. Handy came in too and listened to all the records. They’re perfect—they’re my tops, I think. I wouldn’t call them Dixieland—to me that’s only just a little better than bop. Jazz music—that’s the way we express ourselves.”

Avakian then went to work in getting the album designed and getting the word on the street. It was first featured in an ad in Billboard on September 25, 1954. Avakian’s best known for his jazz credentials but it’s important to point out that he was the head of Columbia’s entire pop album department, so aside from Armstrong and Dave Brubeck, he also had his hands in releases by Judy Garland, Percy Faith, Liberace, and the others included here:

The bad scan of the above ad obscures Armstrong’s image but for those unaware, that’s actually the first cover design for Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy. Here it is from our Jack Bradley Collection:

Avakian and the design team at Columbia bet the farm on this look, using different color schemes for each format the record was released in. Here’s Volume 1 of the 10-inch LP edition:

This was also issued as part of a 7-inch “Extended Play” series:

Volume II of the 7-inch EP:

And finally, yet another 7-inch EP series, divided into three volumes:

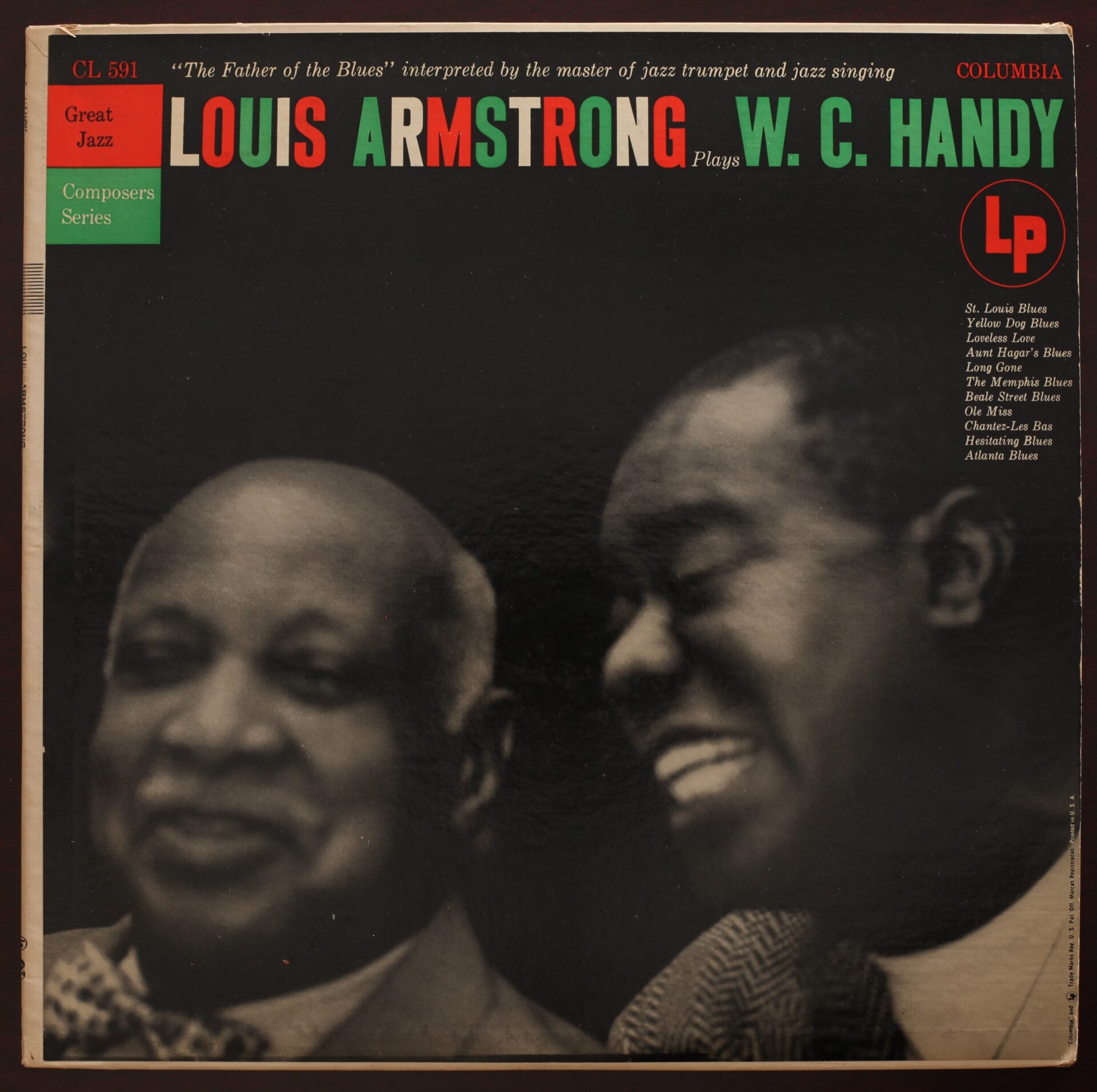

If Guy Gillette was shooting photos at the New York meeting on September 3 and Columbia was advertising the above design on September 25, it can be assumed that the above scheme was already in place or Avakian hadn’t fully examined Gillette’s work yet. But once he did, a call was made to the art department and Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy was almost immediately reissued with a new cover featuring the two titular titans. Here is Louis Armstrong’s copy:

Even after the first September ad, the Handy album didn’t get reviewed until December with Billboard giving it a rave in its December 4 issue and Nat Hentoff laying five stars on it in Down Beat that same week:

By the time the Down Beat review was published, Armstrong was back on road on a grueling stretch of one-nighters that lasted from December 1954 through early April 1955. In many of those stops, Louis was asked to do radio interviews and the Handy album almost always came up. Two such interviews survive in Louis’s private tape collection. The first one is from Billings, Montana and if you’ve made it this far into this article and have listened to the earlier selections, it won’t surprise you that this is from another of the series of tapes that are on the cusp of being unlistenable. It’s still worth sharing, though, because for this one, Louis brought along all of the All Stars except for Arvell Shaw. This is an edited excerpt opening with Louis talking a bit about the album. After a short fade, the next voice is clarinetist Bigard. Asked to name his favorite record of his, Bigard initially names his own “Step Steps Up” and “Step Steps Down” before talking about his favorites on Handy, mentioning “St. Louis Blues” and “Atlanta Blues.” Finally, Trummy Young is brought over and tells the story of playing that extra chorus on “Chantez-Les Bas,” saying “I got carried away” (Louis responds that he got carried away, too):

In early 1955, a somewhat tired-sounding Armstrong sat down for an interview with college student Dick Easton at Kansas State University’s radio station. The station sent Armstrong a copy of the broadcast for his tape collection, so finally, we’re proud to present something in excellent sound quality. Louis talks about making the record in the Wrigley Building, mentions the chorus of friends on “Long Gone” and again tells the “Chantez-Les Bas” story:

Needless to say, the Handy album remained a perennial in Armstrong’s tape collection, dubbed repeatedly to various tapes over the years, though never with one of those wonderful, spoken “disc-jockey” introductions. However, it’s worth pointing out that on the next-to-last tape Louis made just days before he passed away in 1971, he was still listening to Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy, dubbing it and Satch Plays Fats from a 2-LP set Armstrong bought in Japan, Satchmo For You. Here’s his copy:

And here’s Armstrong’s handwritten notes on the contents of the tape, quite possibly the last of his handwriting to survive. This particular tape ended with the first half of an LP of his Decca recordings with Gordon Jenkins. That album was continued on what would be Louis’s final tape, a story we told here. That tape didn’t have a handwritten catalog sheet because Louis passed away in the middle of making it, thus this is one of the last things he wrote:

So there you have it, Louis Armstrong, still listening to and enjoying Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy until the very end of his life. Whether you know the LP, bought the CDs, ordered the Mosaic set, or have never heard it but are now curious, check out Louis Armstrong Plays W. C. Handy today and you’ll agree with Pops that it’s his tops.